What’s the Sahm Rule?

If “sus” was the most popular Gen Z slang word recently, the hottest investing buzzword would be the “Sahm Rule.”

The Sahm Rule isn’t slang (“sus” is shorthand for “suspicious,” by the way) but it’s been all over the investing vernacular like white on rice since it began signaling a US recession following the rising unemployment shown by the Bureau of Labor Statistics report on Friday, August 2nd.

Let’s explore it – and what it might mean for investors.

The Sahm Rule

The Sahm Rule indicates recessions by measuring how quickly unemployment is rising.

Importantly, it’s designed to be an early indicator, versus a predictor, of recessions.

According to the St. Louis Federal Reserve:

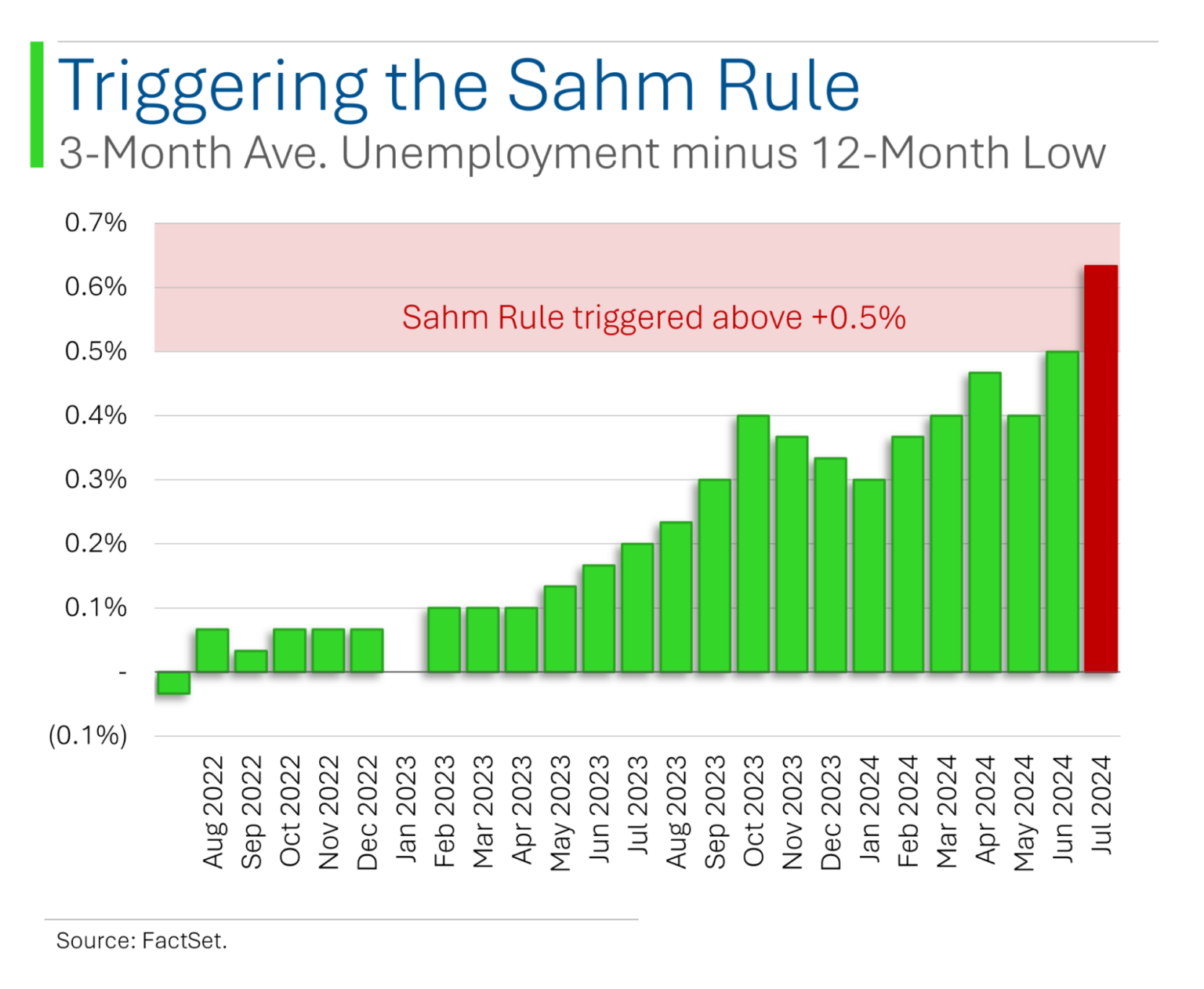

“The Sahm Rule identifies signals related to the start of a recession when the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate (U3) rises by 0.50 percentage points or more relative to its low during the previous 12 months.”

It’s not scaled – 50 basis points would seem three times more meaningful with 3% unemployment than with 9% – but it’s easy to remember and use, which makes for a workable rule.

Unemployment is a linchpin economic number that trickles into many other things. And Sahm found that the change matters more than the raw number – she points out in her Bloomberg column (registration may or may not be required) that unemployment was 3.5% during the 1969-1970 recession, and more than 7% for the 1981-1982 recession.

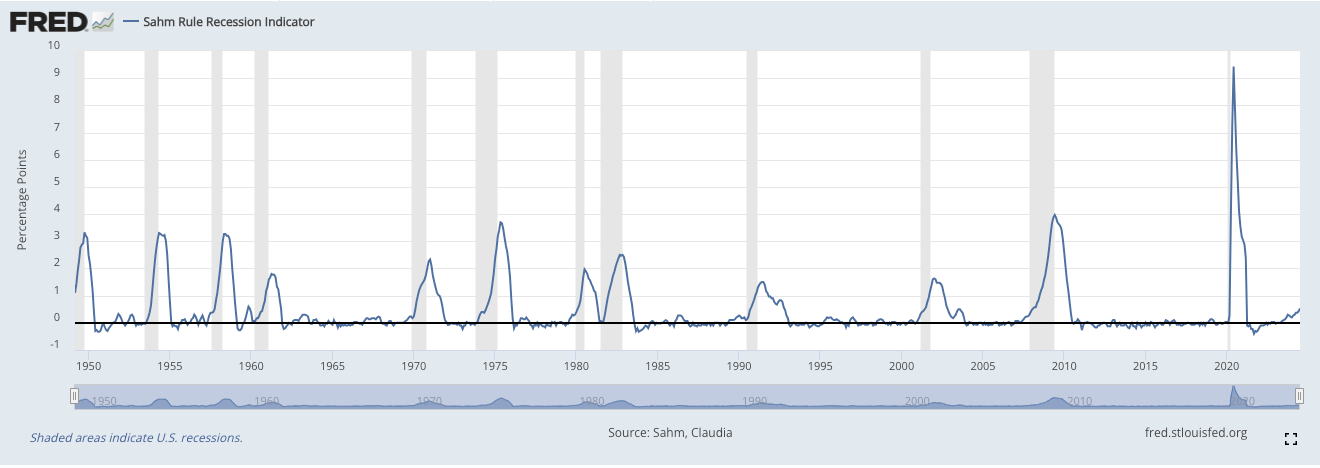

That indicator-vs.-predictor bit is important. If you look at the FRED chart below from the St. Louis Federal Reserve – out of the 12 Federal Reserve banks, the folks in Missouri have the best data site – it’s clear that the Sahm Rule trigger tends to peak right after recessions (which are shaded in gray) end.

But that’s just the peak. The Sahm trigger does start notably rising during recessions – i.e., it does a great job of being flat in non-recessionary times, which seems to indicate a low risk of false positives.

What is a recession?

A recession is one of those things for which the connotation is easy, but the denotation is hard.

And the notion of predicting, or even indicating, a recession is different from what folks in securities markets are used to.

Securities markets tend to be anticipatory: If you think a good thing will happen to a company, it is absolutely imperative that you invest before that good thing happens, because as soon as it does, that goodness will be immediately priced in.

So a securities investor might wonder: What good is a recession indicator in the first place? Wouldn’t a predictor be much better?

Yes, it would, but a) a reliable one doesn’t exist (note inverted yield curve comments below), and b) a recession is a mushier concept than you might expect anyway, and they’re only declared after the fact – at least in the US, by the National Bureau of Economic Research, or NBER.

In older days, recessions were often defined as two consecutive quarters of GDP shrinkage (i.e., negative growth, and please differentiate “negative” from simply “decelerating”). More recently, and some might argue for political reasons, the NBER’s more-inclusive-yet-less-satisfying definition has come to the fore.

In other words, there’s actually no official definition of a recession, even if everyone intuitively knows it means an economic slowdown of some sort. The NBER’s recession definition is this:

“…a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in production, employment, real income, and other indicators. A recession begins when the economy reaches a peak of activity and ends when the economy reaches its trough.”

The NBER may take up to a year after a recession has ended to declare that a recession has happened.

Up against that, an early indicator like the Sahm Rule looks downright speedy.

Now, there’s no playbook on how investors can exploit this early indicator knowledge (or even if it’s accurate – see Sahm’s own warning below), but I’d guess that broadly, if there was some doubt amongst investors as to the state of the economy, but you saw the Sahm Rule triggered before anyone else (impossible, because they can see it, too) or trusted it more than others (this is possible) and were correct in doing so, you might place some bets appropriate for a worsening economy, and profit as other investors later woke up to the same reality as confirming data points rolled in.

Who is Claudia Sahm?

Claudia Sahm is currently at money management firm New Century Advisors, but is known for her work as an economist at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. She was also on the Council of Economic Advisors for the Obama administration, and writes for both Bloomberg and The New York Times.

(Aside: I visited the Federal Reserve Board of Governors once. These folks are really smart.)

Oddly, Sahm says not to apply the Sahm Rule now

Now, the likable thing about Claudia is that while she appears to be making the most of her (deserved) time in the sun, she’s downplaying expectations about her Rule indicating a recession right now. Technically, she says her Rule doesn’t differentiate between rising unemployment because of reduced demand for workers – traditionally, a bad signal that indicates a slowdown – and rising unemployment because of an increased supply of workers, which is a less bad thing.

(NB: It won’t be the only recession rule that’s not applying as usual: The inverted yield curve – which, until recently, had phenomenally good track record of predicting recessions – has failed miserably. Nobody can say exactly why, but many suspect that drastic COVID-era monetary policy actions (possibly additive to prolonged low rates pre-COVID) have distorted the US economy.

Anyway, Sahm technically says that the US economy is showing too many strong data points for it to be in a recession now, but that the risk of a recession soon remains elevated.

She also believes the economy is shaky enough that the Fed needs to start cutting interest rates.

In conclusion

Economics is a complicated, reflexive social science. Investing, a subset of economics, is the same. Ambiguity causes people stress, and there’s always been demand for clear, simple “Rules” that cut through the confusion to cull clarity from the mess.

All things considered, the Sahm Rule, heuristic though it may be, appears pretty good at doing this. It would be unrealistic to expect anything more, in fact.

Curious for more? See Claudia Sahm’s blog here.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.