Does the US Have Too Much Debt?

There is nothing new about the US national debt, and there’s nothing new about talking about the US national debt, but that the interest payment on US debt crossed $1 trillion for 2024 is new.

With interest payments rising and both Donald Trump and Kamala Harris poised to increase the national debt, folks are wondering: Is America’s national debt a problem? And if so, how big?

If you just want a quick answer, JP Morgan Wealth Management says no, you don’t need to worry, at least not too much, about the high US national debt. It’s a little bit bad, sure, JP Morgan’s analysts say, but the dollar isn’t going to crash, inflation isn’t going to spiral out of control, and the US is not going to default.

Of course, there are some who say it will. Peter Schiff is one:

That said, Peter Shiff, well-known as he is, has a bit of a history of being alarmist. I’m glad I didn’t heed his advice in 2011:

I’m not particularly singling out Peter – there are plenty of pundits like him – but his debt concerns in 2011 didn’t come to life. In fact, if you’d bailed in 2011, you’d have missed a wonderful bull market. From the 2011 article:

“If you own dollar-denominated assets, then you’re a fool. It’s really that simple in the black and white world of American fatalism that is the trademark thesis of Peter Schiff, the CEO of Euro Pacific Capital.

“Unfortunately, because we raised the debt ceiling, because we continue to spend money, the cost of government is going to be born by those foolish enough to hold U.S. currency,” Schiff tells Breakout.”

Per Richard Rubin in a front-page article for The Wall Street Journal that’s a bit more centrist:

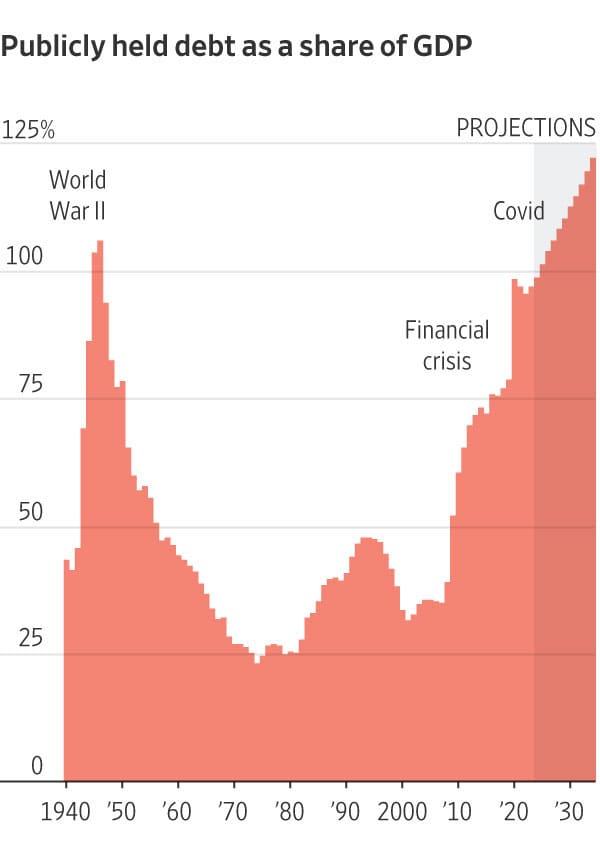

“This year’s budget deficit is on track to top $1.9 trillion, or more than 6% of economic output, a threshold reached only around World War II, the 2008 financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic. Publicly held federal debt—the sum of all deficits—just passed $28 trillion or almost 100% of GDP. “

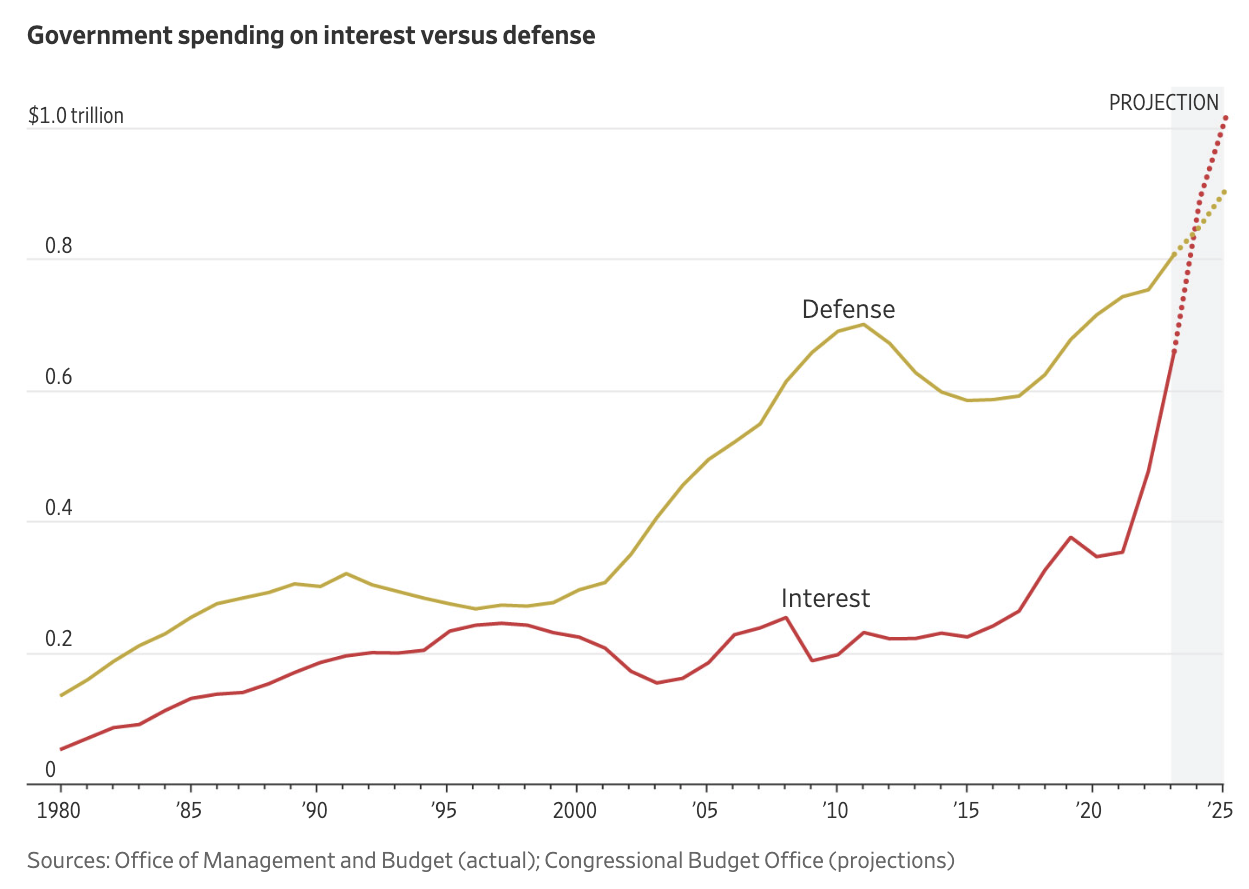

If Congress does nothing, the total debt will climb by another $22 trillion through 2034. Interest costs alone are poised to exceed annual defense spending.”

Was Schiff just a little early in panicking? A graphic in this article follows:

National debts have always received some focus.

Is national debt good or bad?

They’re neither entirely bad nor entirely good: Much as how personal debt is considered OK by most for education (at least traditionally; college costs have arguably gotten out of hand), home purchases, and emergencies, a national debt can be useful for need-the-money-now type situations.

Sovereign debt is comparable in some ways to personal debt, but not in others. If a government is borrowing in the same currency its central bank prints – and that currency is not pegged to any outside asset like gold or another currency (I believe there are actually far more pegs than this list shows) – the government may be tempted to just print a bunch of money to repay its borrowings.

In fact, the US, which has been on and off the gold standard a few times, dropped the dollar peg in 1971. This helped pay off Vietnam War debt, and prompted other countries to de-peg as well, beginning an era of both “fiat” and dollar-pegged currencies. The US’ 1973 deal with Saudi Arabia to price oil in US dollars further solidified the dollar’s role in global trade. (Read up on Bretton Woods for more background.)

But the US can get away with it, or at least has so far, by virtue of being the major reserve currency and also the major transaction currency of the world.

For sketchier countries, the market has slowly figured out that the ability to inflate currency to repay debt isn’t an economic win for bondholders (who get paid back in highly devalued currency), and mostly now require emerging market countries to denominate loans and bond transactions in US dollars.

Anyway, this is a very long way of saying that while most people would agree with the phrase: “A lot of national debt is bad,” the extent of “bad” and how much “a lot” actually is are highly debatable.

In relation to the graphic above, and as Morgan Housel once noted, the US had similarly high debt load around World War II, and simply grew its way out of debt.

Can it always?

The rub of the Journal article is that presidential candidates no longer seem to care.

Are politicians giving the people too much of what they want – and is it coming at the expense of future generations?

Rubin notes that both candidates have promised things that will cost big money. Based on currently professed plans, Kamala Harris would spend slightly less and also offset more spending with tax increases and cuts elsewhere than would Donald Trump, but both candidates would be net increasers of the deficit and debt.

To be fair, one challenge they each face is that it’s considered political suicide to reduce Medicare and Social Security – the biggest government outlays, but also extremenly important to an aging base of voters.

In simpler terms, to win voters, nobody seems to want to cut spending much.

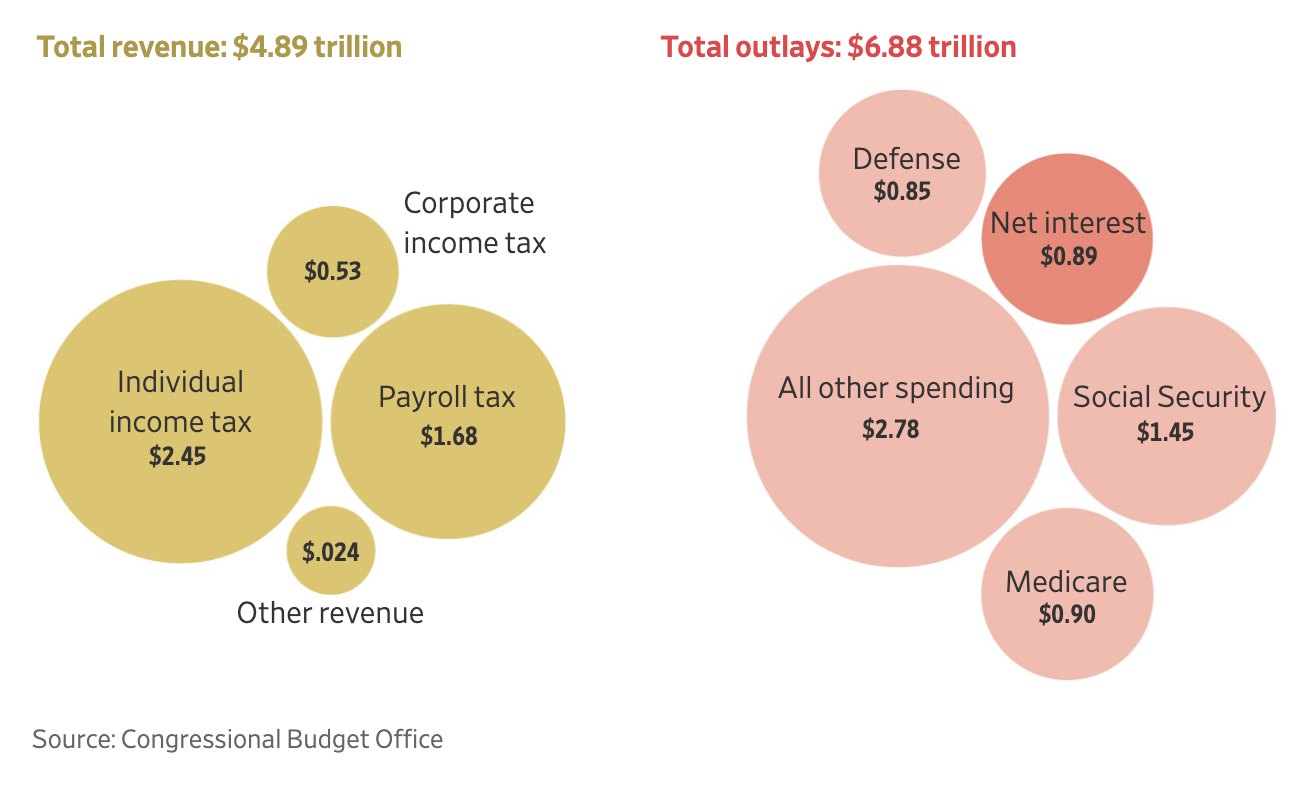

As the WSJ graphic above shows, the year-to-year US budget is nowhere near balanced – expenses exceed tax receipts by just about $2 trillion, and that overage must be financed by debt.

For whatever reason, the US government, unlike many companies, did not make special efforts to refinance its debt several years ago when rates were very low, so interest payments – already one of the four “biggies” among national expenses – will grow at a disproportionate rate.

(Sharp-eyed readers may note that the Journal’s graphs slightly conflict: The bubble chart shows net interest already surpassing defense, if slightly, whereas the line chart below shows it about to surpass it. I’d guess it’s a simple issue of slightly different data sets, and it really doesn’t matter in terms of the overall point the article makes.)

In a sense, politics is about giving the people what they want.

But which people? Just the voters alive now? Or future generations?

I was recently in Argentina, where decades of government spending and giving huge swaths of the population “jobs” with the government has wrecked what was once the sixth-wealthiest country in the world.

Only now, at rock bottom – with few willing to lend in any currency – Argentina is trying a get-tough-and-take-the-pain program to rebuild its credibility, guided by flamboyant libertarian Javier Miliei.

I side more with JP Morgan than with Peter Schiff, but it’s also true that trees don’t grow to the sky, and the US’ borrowing ability is only as good as its relative credibility – which, so far, has stayed high.

But I see the dilemma.

People want low taxes.

People also want expensive things: healthcare, elder care, education, roads, defense.

Can politicians give us both at the same time, sustainably? We may eventually find out.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.