What Does a More Miserable World Mean for Investors?

Gallup released its World Happiness Report (download link here) a few months ago (I caught wind of it through Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Pump Club health email), and things aren’t looking good for the US.

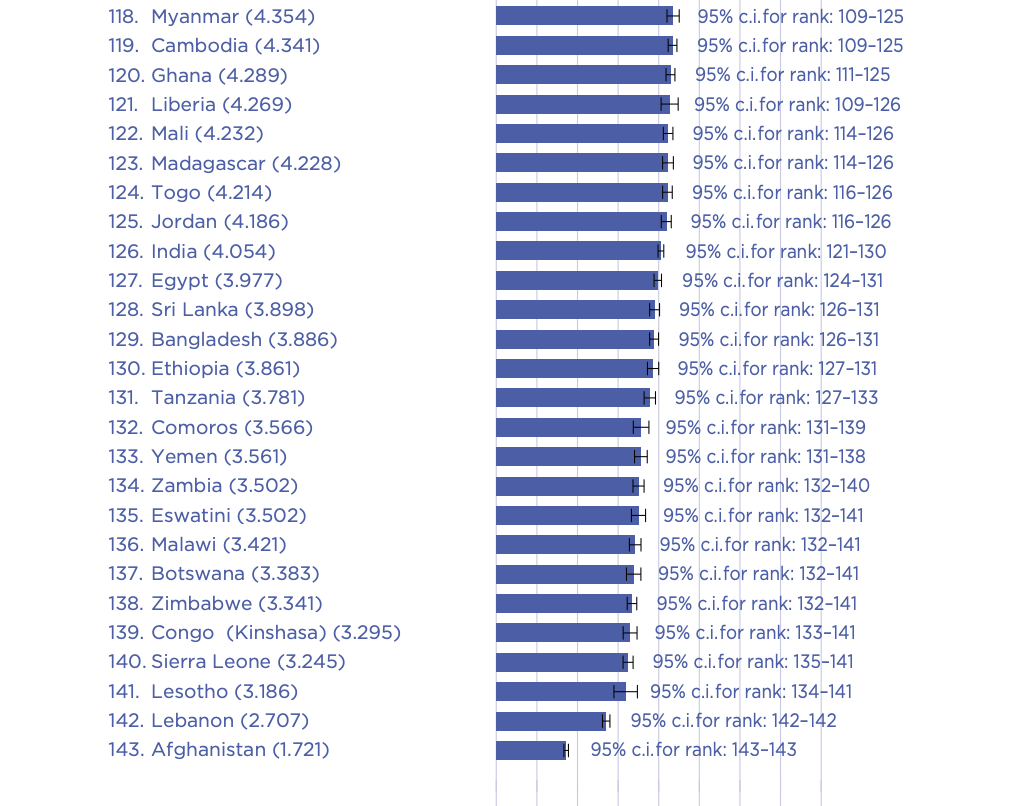

Granted, out of the 143 countries that Gallup surveyed, the US clocked in at #23, which isn’t terrible, although it’s the first time the US has fallen out of the top 20 (the US was #15 last time).

If you’re curious to see the least happy countries – and come on, who isn’t? – here’s the tail end:

Before I go much further, a note: Measuring happiness is very controversial among academics. More on this topic here, here, and especially here if you’re curious.

Another question is whether happiness is the best aspect of well-being to measure in the first place. Multiple nations (the UK, New Zealand, Israel, and I’m sure more) are, in fact, asking some version of this question in a quest to create an alternative-to-GDP measure of national well-being. The idea feels good: It’s perfectly reasonable to care about the happiness/satisfaction/contentment/mental well-being of your populace, and to want to improve it.

It’s just tricky to quantify.

But difficulty of quantification doesn’t mean a thing isn’t real. It just means it’s hard to quantify. I could say that avocados, skiing, and friendship are all important to me, for example. All true. But I can’t put a number on any of them, and wouldn’t know how to add them up or compare them.

Interestingly, according to the World Economic Forum, unhappiness is easier to measure than happiness, which makes some sense – and arguably forms one selling point of a welfare state, theoretically: Welfare doesn’t boost happiness; it just tries to reduce unhappiness.

The US is in a happiness free fall

But for now, let’s play along with the study.

I may be a rube, but I do feel like the Gallup survey results are directionally accurate, even if accidentally. The rub is that American happiness declined more than that of 90% of countries reporting happiness changes.

According to Gallup’s findings, we’re in a happiness free fall.

America: A great place for old folks; less so for Gen Zs

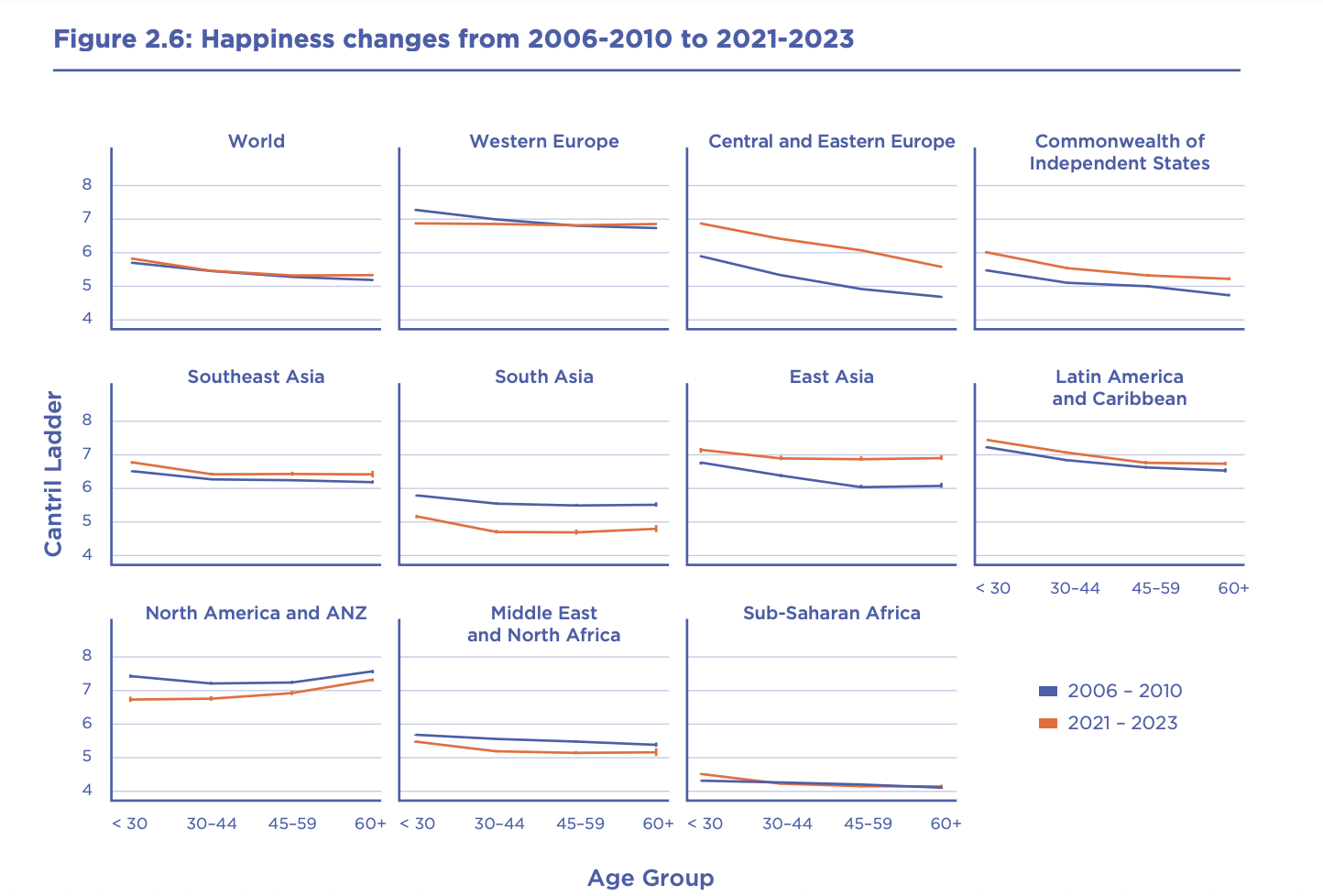

Gallup’s most recent survey looked at happiness by age groups for the first time, and interestingly found that for people 60 and over, America is still in the top 10 worldwide.

Meanwhile, for Gen Zs, it’s 62nd.

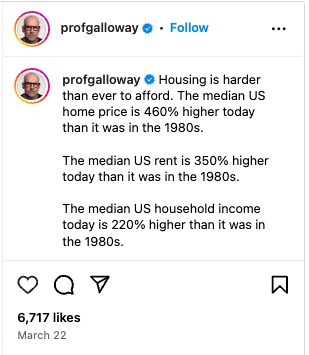

I should probably resist assigning a story to this data, but let’s remember that Boomers came of age during a tremendous and multi-decade economic boom for the US. They were in their prime earning years during the late 1990s dot.com peak, whereas Gen Xers like myself were new to the workforce, and Millennials were still in school and Gen Zs were just starting to be born.

Boomers bought stocks before they rose and bought houses when they were affordable – and are sitting on massive capital gains in both. They’re digging the American life.

Economically, Gen Z may be feeling burned from the 2021 crypto-and-meme stock bubble, jaded about how the economy seems to work, and frustrated that the Boomers’ real estate capital gains have made housing unaffordable for everyone who hasn’t bought a house yet.

Besides, Gen Z is the loneliest generation ever recorded in the history of the world. I’m not sure how long the world has been “recording” loneliness, but you get the point.

And it really is the point: The Harvard Study on Adult Development – the world’s longest study on happiness and well-being – found that the most important ingredient in human well-being is relationships.

Seeking “relationships” over social media is like trying to get a tan by sitting under a reading lamp: It has a veneer of logic to the uninformed, but it’s not how nature works.

Before I segue to economics, one more diversion: Women.

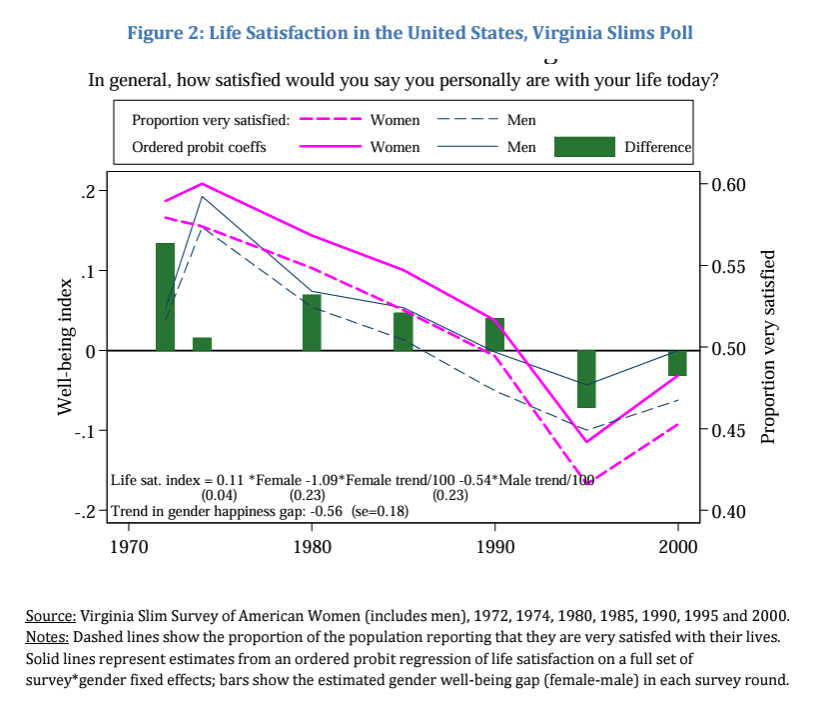

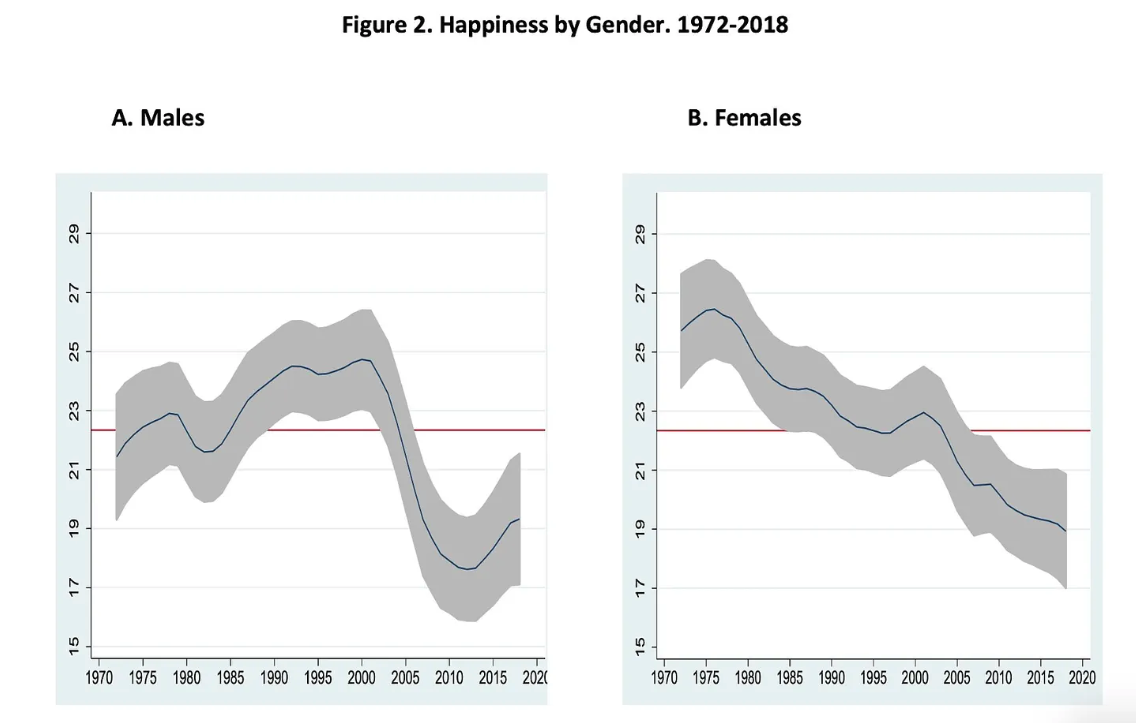

The women’s happiness paradox has been much discussed, so I won’t wax long on it here, but the gist is (according to research drafted in 2008 by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, both of Wharton) that from 1970 until today, women have very clearly made huge strides in a “liberation” sense – in fact, nobody even really uses “women’s lib” anymore, because women have been liberated. While they still earn less, women now significantly out-graduate men from college (read: they’ll be earning more soon), hold senior-level business and political positions at a much higher rate than a generation ago, have birth control accessible, and are simply afforded more respect in society.

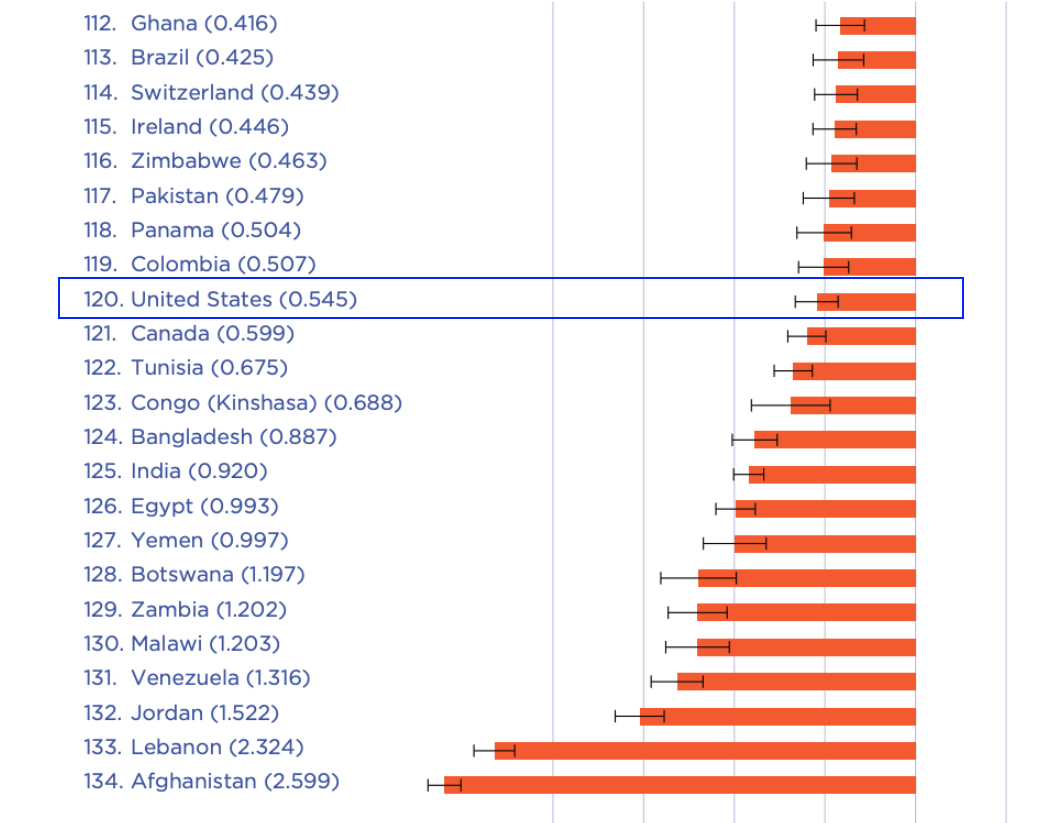

Somehow, they’ve gotten more miserable:

And it’s not just this study.

A 2023 paper by Sam Peltzman of The University of Chicago called The Socio Political Demography of Happiness found the same thing, basically:

Much ink has been spilled speculating on why women – who traditionally were happier than men on surveys – are now more miserable. Some progressives seem to take issue with the findings. Some traditionalists say women’s brains are different from men’s, and that swapping kids and marriage for a career ends up less fulfilling than it was supposed to be. Or, causes may be more practical: According to this working paper (a working paper has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal), in households where both men and women work, women spend 40% more time on caregiving tasks than men.

I don’t know the answer to the paradox, and I’m biased in that I’m sensitive to the struggle of women, but regardless of how my brain works, as a human, if I were working full time and was also the primary caretaker, I’d feel stressed, too.

Let’s not forget that for most of human history, people lived together in extended families, which absorbed elder and child care duties more easily. Remove that family help net, add career obligations, and it makes sense that women feel frazzled.

Less happiness = less trust?

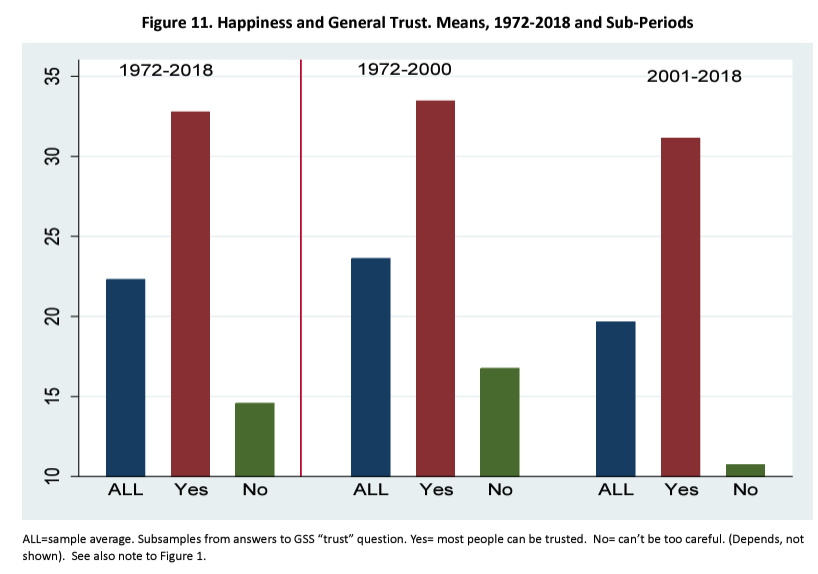

But back to economics. One problem, per Sam Peltzman, is that happiness and trust tend to decline together. The red bars below represents “yes, most people can be trusted” responses, which have declined since the early 1970s – years I’m now envisioning as amazing party years after seeing all of this data about how happy everyone used to be then:

If this graphic is correct, a less happy world is a less trusting world. And economic transactions require trust. Or, at least, the more trust, the easier the transactions.

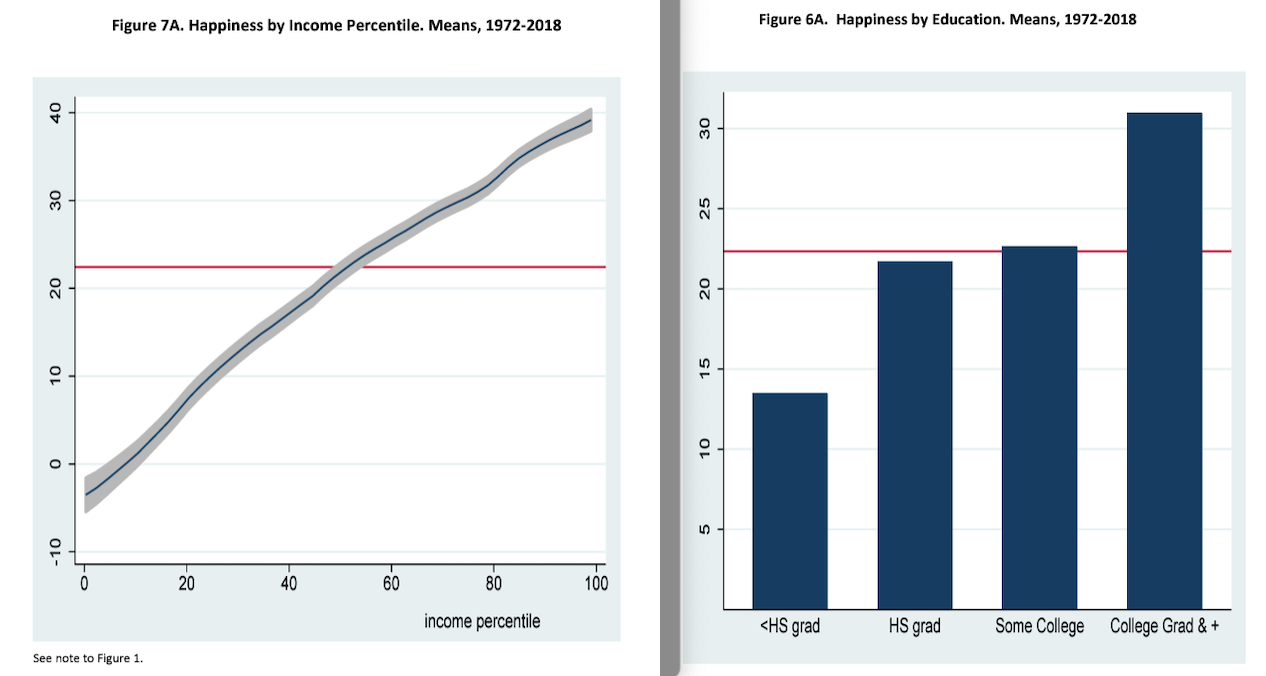

Proviso: I’m skimming these studies, so it’s likely I’ve missed some details and explanations. That said, one thing seems odd. Sam’s data show that happiness increases with wealth and education:

But jumping back to the Gallup data, the world has become notably less happy than it was in 2006, yet it became wealthier and more educated during that time. (To be fair, Sam’s data is from the US population, though the principles would seem like they’d apply to people everywhere.)

Go figure.

The truth is, it’s unknowable exactly what a more miserable world will mean for investors.

Perspective 1: Unhappiness is bad for the economy

Broadly speaking, if happiness erodes trust, presumably reduces collaboration – whether domestically or internationally, if I don’t trust you and you don’t trust me, we’re less likely to trade – correlates with income inequality (regions with greater income inequality have reported lower happiness than more uniform regions, even though the relationship between income inequality and happiness is not linear, at least according to this study done in China on US data), the US’ rapid erosion in happiness – at least among Gen Zs, who will eventually become our most economically active cohort – is bad news economically.

Perspective 2: Unhappiness is good for the economy

Italian political scientist Stefano Bartolini, in a book chapter called “Unhappiness as an Engine of Economic Growth,” paints a bleak case, at least with reference to the US, China, and India – all of which have gotten a lot richer and a lot less happy in recent years. I just peeked at the abstract, but Stafano’s case (and I’m paraphrasing liberally here) seems to be that we’ve become miserable, consumerized wretches, hell-bent on comparing ourselves on social media, and having replaced wholesome, non-monetary sources of well-being with “market” sources – which I take to be a polite, academic way of saying we’ve swapped meaningful moments of in-person engagement with friends and family for buying stuff that would look good in our next TikTok flex.

Again, I’m paraphrasing Stefano, but his point seems – well, first, it seems to be something a European would say – but it seems to be that the upshot of being over-motivated by money is that we’ll work harder to get it.

Who’s right? I think both perspectives contain some truth. I tend to think Boomers would agree with Perspective 1 more and Gen Z might agree with Perspective 2.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.