The stock market has a user error problem.

The potential for big money is there: $100 plunked into the S&P 500 in 1925 (before it was even the S&P 500) would be worth nearly $1,600,000 today.

These returns would seem almost like free money: anyone can buy and hold the S&P 500.

Yet few people do. Dalbar Research found that from 1988 to 2018, the S&P 500 earned 10% per year – yet the average stock fund investor earned just 4% per year.

Someone with $10,000 and either the tenacity or mindlessness to just buy and hold the S&P 500 in 1988 would have $174,000 three decades later, even without reinvesting dividends. But at that “average” rate of 4%? Just $32,000.

Ouch.

The stock market, over the long run, has done phenomenally well. But individual investors fail to capture much of that goodness.

Well, on occasion they do. If you read Hannah Miao’s Wall Street Journal piece “Who You Calling Dumb Money? Everyday Investors Do Just Fine,” you know that per Vanda Research, the average investor’s portfolio is up 150% since the beginning of 2014, modestly exceeding the S&P 500’s 140% gain.

It’s heartening, if exceptional. And one study (Ivkovic, Sialm, Weisbenner, 2008) even found that households with less diversified portfolios outperformed households with more diversified portfolios.

But triumph of individual investors is not the norm. Professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean, kingpins of research on individual investor performance, found, for example, that when individual investors sell a stock and buy another, the “replacement” stock underperforms its predecessor by an average of 23 basis points per month in the following 12 months.

Protected by academic jargon, Barber and Odean diplomatically describe this effect as “perverse selection ability.” But what they really mean is that people are colossally bad at picking stocks.

“With some exceptions … the evidence indicates that individual investors are subpar investors.”

Brad Barber and Terrance Odean

Active fund managers – being people, too – aren’t really better. According to S&P, roughly 60% of active managers lost to the S&P 500 during the first half of 2023. Over the past three years, 80% did. Over the past decade? 87%. And the past 20 years? 94%.

Part of the reason beating an index is so hard is that just 4% of stocks drive all the gains, as I mentioned in this piece discussing Hank Bessembinder’s research. It’s similar for time periods: if you missed the best 0.19% of trading days over the past 20 years, your returns would be 55% lower. Missed the best 1.9%? 93% lower.

What lessons have experienced investors learned?

Barber and Odean blame two forces for individual underperformance: poor stock selection and trading costs. These days, trading fees are at or near zero in most cases (equity trades are certainly free at BBAE). That removes some of the downside of frequent trading, but not all: logically, if individuals tend to make poor decisions around security selection, the fewer investment decisions they make, the better – just like how it’s best to shut up when you notice that whatever you’re saying in a difficult conversation is only making things worse.

Interestingly, many of the same lessons unearthed by academic research have been converged upon by everyday practitioners, too.

Charles Schwab, as part of celebrating its 50th anniversary, surveyed 3,006 customers. It broke them into two groups: those who’d been investing since before 2000, and those who started after.

To be clear, this was a survey, and not a study, so it’s relaying what people say. Among the experienced investors, though, the convergence to the academically “proven” principles was uncanny:

- 87% would choose long-term investing to allocate an extra $100,000 today

- 86% describe their investing style as “tortoise” rather than “hare”

- 86% have learned to not let their emotions affect their investing (relative to when they started)

- ⅓ said that the biggest contributor to their investing success was having patience to ride out volatility

You can read more from the Schwab survey here.

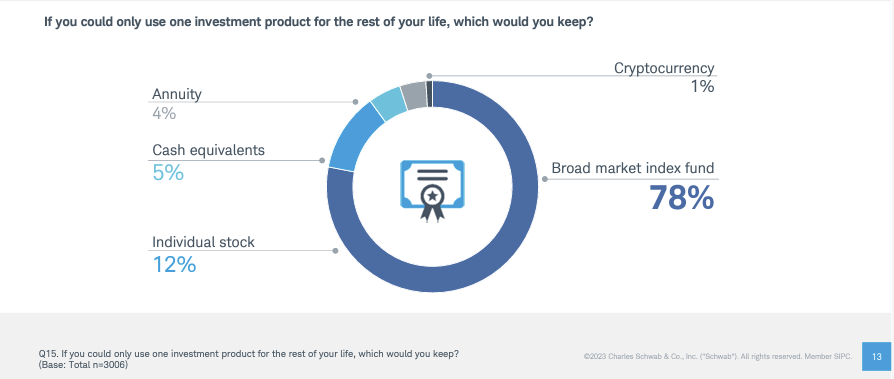

Schwab also asked a weird question: “If you could only use one investment product for the rest of your life, which would you keep?”

This is a stilted, contrived question: nobody in real life would ever be limited to one “product,” and Schwab’s answer choices mix products and asset classes, which feels a bit iffy.

But if we interpret this to mean “What would you start with as your portfolio baseline?” it makes more sense that 78% chose a broad market index fund. (I’m supposing the 5% who say “cash” are either of advanced enough age that they’re in liquidity drawdown mode, or else they’ve got bunkers stuffed with dehydrated food and Guns & Ammo back issues.)

I use broad market investing as my baseline, too.

Broad-market baselines tap the power of the 10.3% annualized return that turned $100 into $1.6 million in my introductory example.

Broad-market baselines sidestep the illusions of trying to find the 4% of best stocks, or jumping into the market for the best 1.9% (or even 0.19%) of days.

Broad-market baselines, both academics and experienced investors alike would tell you, are the wholesome, broccoli-and-lean-meats way to invest.

But what if I told you there was a better way to do them?

BBAE’s better baseline

If you know the term smart beta, you know that indexes that weight companies according to market cap (like the S&P 500) don’t always give the best performance. Sometimes they do – company size is one performance-driving factor per academic research – but sometimes indexes built with other “rules” give more risk-adjusted bang for the buck.

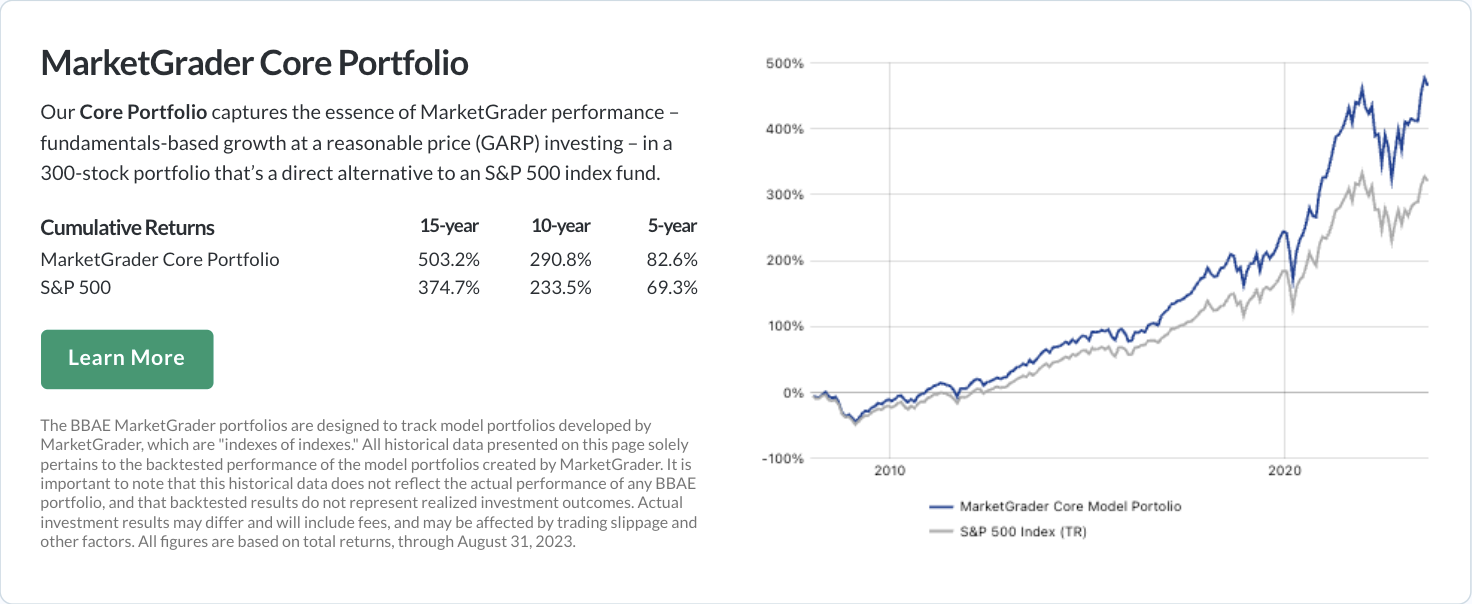

BBAE has partnered with a smart beta pioneer called MarketGrader to create three portfolios that we collectively believe offer a better-than-S&P 500 baseline.

MarketGrader has a model that rates all 41,000 stocks around the world. MarketGrader uses 24 wholesome, fundamental factors – factors well-documented in academic literature – and over the past 10 years, 47 of the 52 indexes it’s created have beaten their benchmarks.

We wanted outperformance for BBAE account holders, so we wanted MarketGrader. We’ve just launched these portfolios – one standard (Core), one growth-leaning Growth Compounding), and one income-leaning (while targeting market-level growth at the same time; Growth and Income) – which you can read about here; I’ll share a screenshot from the Core’s description below.

We’ve just launched the BBAE MarketGrader Core Portfolio, so actual performance is beginning right now, but as you can see, the index it follows has handily beaten the S&P 500 in tests.

Whatever your investment proclivities, I urge you: take a lesson from academic research. Take a lesson from experienced investors. Get started investing. Be consistent. Stay calm and don’t take needless risk. And get a market “baseline” investment for your portfolio.

It doesn’t have to be one of BBAE’s (smarter) smart beta offerings, but I personally believe they’re an excellent place to start.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. Investing carries inherent risks. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.