Surprise! Most Stocks Lose Money

If you’re buying individual stocks, the stock market tends to be a brutal place.

If you’re buying stocks in aggregate, the stock market tends to be a miraculous place (at least if you’re patient).

If you’re either skillful or lucky, you can outperform the market by choosing great individual stocks, but most investors can’t, even though they think they can.

If I had to summarize equity investing in three sentences, I might choose these.

Mathematically, they’re about the probability distribution of stock returns, but more on that in a moment.

Stock Investing Truth #1: Picking individual stocks has poor odds

In support of the “brutal place” line, I came across a study from Arizona State University professor Hank Bessembinder showing that from 1926 to 2019, 58% of stocks lost investors money. Here’s the paper:

In other contexts, “58%” would be a scary number. Imagine if:

- 58% of diners got slightly sick after eating at a restaurant

- 58% of taxi drivers in a city would take you near your destination but only to within, say, a one-mile radius, meaning you were still left with a long walk

- 58% of babysitters in a town would fall asleep while watching your kids.

You might think twice about using these services (and you’d be especially reluctant to leave the kids with a sitter while you take a taxi to dinner).

Granted, these are both binary and point-in-time events, and investing is neither. We can size positions according to the risk we can bear. And unless we need liquidity immediately, we can sit and wait while stocks go up, down, and back up again.

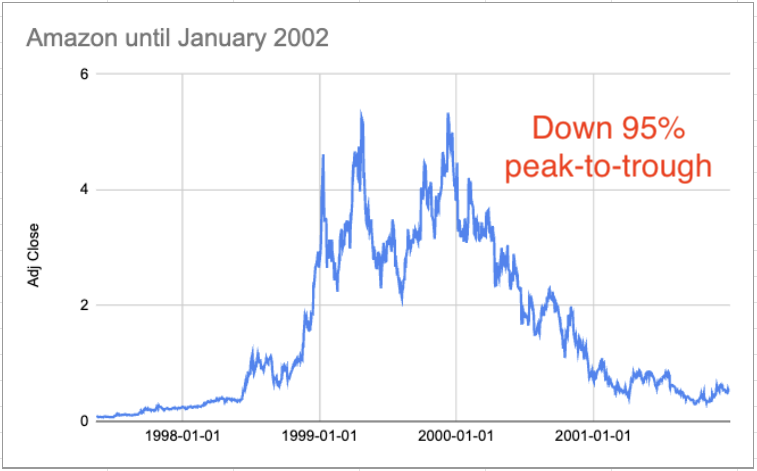

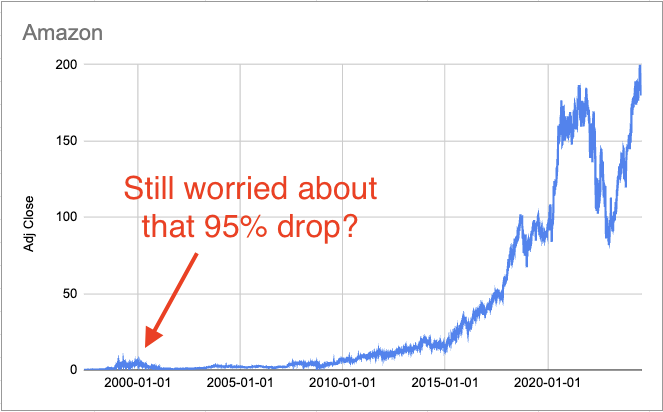

Amazon (Nasdaq: $AMZN), for instance, is a poster child for waiting through the bad times. It declined 95% when the dot.com bubble crashed.

Some media headlines said the company was done for – just another bubble stock collapsing, as bubble stocks are prone to do. Eventually, the company proved the doubters wrong:

To be fair to the doubters – and I don’t have data on hand to back this up – most of the late ‘90s tech startups, especially the small ones, fell and didn’t get back up. Even apart from the tech bubble, Morgan Housel noted that 40% of US publicly traded companies have gone to zero – which, in many ways, is a more chilling stat for those buying individual stocks than Bessembinder’s “58% lose money” figure.

The Amazon example is highly cherry-picked, in other words.

Stock Market: Pareto Principle on steroids

And speaking of Bessembinder, if you’re a BBAE Blog reader, you’ve seen me mention his other finding: Just 4% of US stocks have been responsible for 100% of gains. Sloppily amalgamating the Bessembinder findings with Morgan’s stat gives us a distribution roughly like:

- 40% of stocks go to zero

- 18% of stocks lose money, but don’t go to zero

- 38% of stocks tread water

- 4% of stocks make investors money

Again, this is rough math. And it’s math that describes the past; the future could always differ.

But I believe it will directionally hold in the future because it shows a core truth about the extreme Pareto-ness of investing.

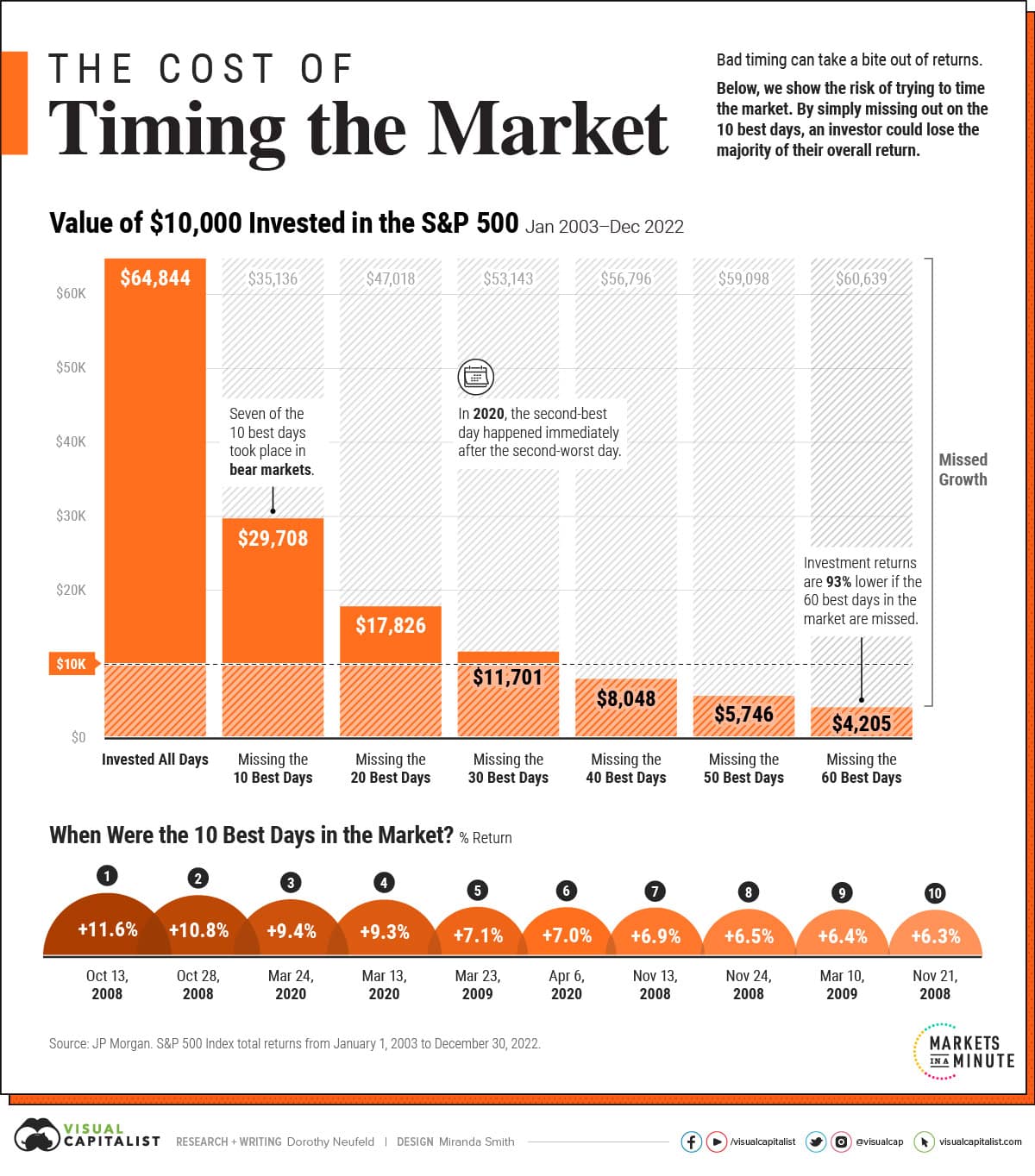

Incidentally, as I’ve also mentioned here before in commenting on a great Visual Capitalist chart, missing the best 1.2% of trading days in the S&P 500 over the past 20 years would have cost you 93% of your returns.

4%.

1.2%.

These are small numbers.

It’s silly to imagine a gigantic crew boat (which I just learned is called a racing shell) where only 4% of the rowers are padding forward and making any progress. And even more ridiculous to picture 93% of the boat’s forwarded progress happening during 1.2% of the rowing time.

But in the stock market, it happens.

Stock Investing Truth #2: The stock market does amazingly well over time

One of my public speaking stats is that based on the long-term historical return of the US stock market, if you’d given a baby $500 in a no-cost S&P 500 mutual fund or ETF 70 years ago (such a thing wouldn’t have been available 70 years ago, but play along), that $500 would have grown to almost $500,000 by the time that person was 70.

Shave a little off for real-life fees, but you get the idea: You don’t need to do anything fancy to retire wealthy if you can shove some money in the market at an early age. Of course, that’s often easier said than done: Young people often battle student debt, pressure to spend on clothes, cars, and the like to impress mates, and simply a lack of knowledge of the power of compounding. (I studied finance in school and still didn’t grasp the true power of compounding until later in life.)

Stock Investing Truth #3: Some good or lucky investors (massively) outperform the market

The first two truths are benign: The first is cautionary and the second inspirational. This one may be risky in a tempting sort of way, much like how slot machine algorithms pay out a little extra early on to hook you. (Slot machines are an interesting study in returns distributions in their own right; they often return 90% or more of their intake to customers, but those returns are highly skewed. A machine may pay out $900,000 after taking in $1,000,000, offering various token payouts along the way.)

There are many examples of successful investors. Just a few include:

- Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: $BRK.B) has returned something like 3,800,000% since inception, and the returns would be much higher if the preceding Buffett Partnership’s returns were included (Buffett’s best years were in the 1950s).

- Ted Johnson, a middle class UPS worker who retired in 1952 and never made more than $14,000 per year, donated $70,000,000 to charity in 1991, which would be something like $160 million in today’s dollars. He invested in UPS.

- Ted Weschler, who now works for Warren Buffett, grew his IRA from $70,000 to $264,400,000. (Ted subsequently chose the noble path of working with the world’s greatest investor, sacrificing higher potential pay for this life honor. With such IRA results, I’d be tempted to go for the quick buck by peddling some “James Early’s Retirement Maximizer”-type program.)

I can’t confirm that UPS Ted had superior investment selection abilities (there may have been some luck involved, and it’s generally unwise to go all-in on one investment), but I’m guessing his financial discipline was nothing short of phenomenal. Buffett and Buffett’s Ted, meanwhile, clearly appear to be highly skilled investors.

In the Efficient Market Hypothesis era, these statements would have been highly contested. “These guys are just outliers… millions of people invest in stocks, and a few of them, mathematically speaking, are going to do incredibly well, but it’s from luck and not skill,” the EMH crowd would have said. It’s not entirely true, but it’s largely true: There’s a lot of survivorship bias out there, and success stories tend to get circulated.

What should you do as a stock investor?

It’s not untrue, is it? Still, not a recommended strategy. Screenshot: Fox News

We don’t give individual advice here at BBAE, but the beauty of investing is that this question has no universal answer. A few points I can think of:

- Be skeptical about individual stocks

- Be optimistic about the whole market

- With so many investing styles out there, it’s hard to generalize about equity selection, but if you’re buying individual stocks, keep in mind that:

- The odds are against you

- Humans have a long and well-documented list of cognitive biases that derail their efforts for successful investing (one Barber and Odean study is here; it’s worth reading more).

- Besides the risk of buying one of the 58% of stocks that either loses money or goes to zero, investors lucky enough to find winning investments tend to get in and out of them at the worst times. I’ve mentioned a Dalbar Research study before showing that, roughly from the early 1980s to present, when investors could have earned 10%+ annually by simply buying and holding an S&P 500 mutual fund, the average US mutual fund investor earned just 4% annually.

- Warren Bufffett’s advice about imagining you have a punchard that lets you only buy 20 stocks your whole life points you in the right direction: You’re facing tough odds when buying individual stocks, so be as sure as you can be that you’ve done your homework, see (with conviction) something the market doesn’t see or – more commonly – doesn’t fully appreciate, and size your position commensurate with your conviction and tolerance for risk.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.