The Worst Idea in Modern Finance

Don’t get me wrong about this.

Trading is good. (It’s especially good if you trade with BBAE!)

Securitization, in fact, is an unsung hero of human progress.

We tend to look at physical inventions – the wheel, movable type, the computer, the curling iron – as moving society forward. For intangible progressions, we’d throw in concepts like language, systematized education and health care, and democracy. Maybe money.

But business, perhaps for its initial connotation as the domain of greedy hawkers, has tended to get short shrift in the public psyche.

I am going to criticize the NYSE’s plan to keep its Arca exchange open for 22 hours per day. It’s my opinion. Yours may be better.

And I’m not entirely going to criticize round-the-clock trading: Practically, 24-hour trading is coming, no matter how we feel about it. It’s at best a win for foreign day traders living in far-off time zones. They can now “day” trade in US stocks in their actual daytime – probably with other foreign day traders, and probably with low liquidity and huge spreads. (Foreign investors own as much as 40% of the US stock market, but I’d wager the portion owned by foreign day traders is quite small.)

But it’s harder to declare this a helpful move for humanity. We don’t need more liquidity. And too much liquidity is a distraction from more important things.

Philosopher kings or philosopher snobs?

Business and markets deserve more credit for moving society forward than they get.

The business class, wrote Aristotle, was “the lowest of the low.” Similar for Chinese philosopher Ban Gu, who placed the merchant class – shāng or 商“ – at the bottom of China’s “four occupations.” (An ancient Chinese saying, 重农抑商 (zhòng nóng yì shāng), means: “Promote the farmer; suppress the merchant.”)

Europeans agreed that commerce was to be despised, at least until the mid-1800s.

This disdain spread into education in a way that still persists. When systematized education began in Europe, it was for the wealthy, who tended to have connections to government or church. One of the first academies was Antoine de Pluvinel’s Académie d’équitation – in name, an equestrian school, but in practice, an all-around school for French nobility – which taught riding, manners, lute playing, and math. The sorts of things French rich people needed to know.

I am not against lute playing, for the record.

It took a long time for Western education to come down from its aristocratic roots. Antoine founded his Académie in 1594, and today, 430 years later, only 26 American states require a financial literacy class in high school.

My point is that we overlook the contribution business – which is more than hawkers and carnival barkers, though it includes them, too – makes to human progress.

And right after money, securitization has probably been the biggest commerce-related contribution to mankind.

All investors used to be long-term investors

“Securitization” sounds like a deep-in-the-weeds-type thing, but it’s not.

In the old days – which still exist in societies without capital markets – you either owned a company or you part-owned a company. Owners tended to be operators, and any financial investors (investors who don’t operationally participate in a business) were virtually always long-term investors rooting for the same outcome as the owner-operators.

This system is actually better than a capital market in a purity-of-motivation sense: Everyone’s focus is the long-term economic well-being of the company.

But it’s limited, for several reasons:

- It tends to foster a lot of little owner-operator businesses because pulling together capital for larger enterprises is difficult

- Would-be investors (and owner-operators) are mostly limited to deals sourced within their personal spheres

- Diversification is out of reach for almost all investors. An investors would need very substantial capital, motivation, and social connections to overcome the high frictions of sourcing and buying shares in many different private businesses

- Middle class investors are mostly left out, because they don’t meet the table stakes for investment in such a high-hurdle system

This is a recipe for low societal GDP growth.

Gallup found that 62% of American households own stocks (as cited by Visual Capitalist).

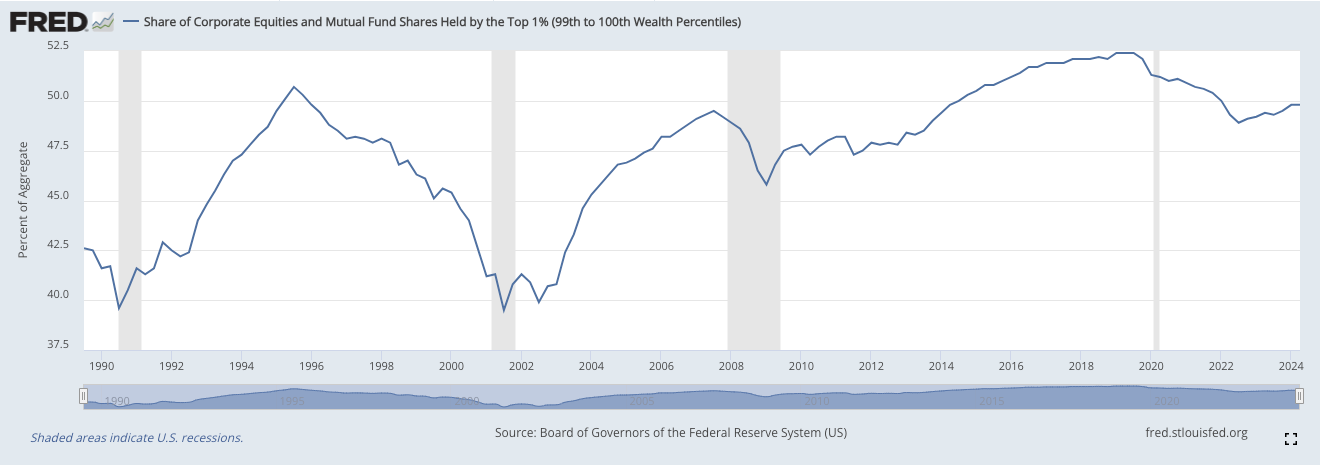

Now, the wealthiest 1% of US households own half of US household-held stocks by value (see graphic below), there’s still a lot of investment going into companies by regular Americans – who own roughly 30% of US equities by market cap directly, and between 70% and 80% (depending on whose data you trust) indirectly.

It may not be dignified enough to teach to schoolchildren, but chopping assets into smaller pieces – securitization – and creating exchanges and platforms for trading those pieces enables investment-seeking enterprises to accept smaller investments, and provides more investment opportunities and easier diversification for all investors.

Trading: Too much isn’t good, either

A saying in medicine: The dose makes the poison. And the cure.

Liquidity is wonderful for getting otherwise-fence-sitting investors to invest. This transfer of money from savings accounts or mattresses and into more productive investments like stocks helps the overall economy. At least to a point.

Multiple studies have shown that while owning many stocks for a long time – broad-market long-term investing – has been wonderful for investors, investors do a terrible job of individually buying and selling individual securities. And the more frequently they buy and sell, the worse they tend to do.

See Trading is Hazardous to Your Wealth: The Common Stock Investment Performance of Individual Investors (Barber and Odean, 2000) for some data on this. Dalbar Research has also found a similar pattern: The more frequently a household trades, the worse its returns.

In Do Day Traders Rationally Learn About Their Ability? Barber and Odean (along with Yi-Tsung Lee, Yu-Jane Liu, and Ke Zhang) found that between 1992 and 2006, 95% of Taiwanese day traders lost money. (And to answer the title question, no, they don’t rationally learn: “…many persist despite an extensive experience of losses.”)

⅓ of investors trade while drunk

And then there’s this, from a MagnifyMoney survey: 32% of US investors have traded while drunk. In fact, 59% of Gen Z investors have.

By tempting trading at all hours – especially hours when investor judgment is not at its best – near-constant liquidity could do more harm than good.

And come on: Even in our interconnected world, how frequently is there long-term news happening in the middle of the night?

Sometimes, yes. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, wars, chemical plant fires, elections, and other news events that move companies, sectors, and markets happen overnight.

But not that frequently. Most “breaking news” ends up being noise in the long run. And do we want a society where people are motivated to stay awake just in case this night happens to have market-moving news?

A huge trading window will bring in more noise, not more information. (Informed trades are those truly carrying superior information, whereas the dude drunk trading after his late-night McDonald’s run is a noise trader.)

24-hour trading is coming, like it or not

I probably sound like a curmudgeon. Or maybe like a horse-and-buggy guy at the advent of the car. But unlike the car, which was a huge step forward for mankind, I don’t think 24- or 22- or any extended hours trading is. More likely, it will tempt activity bias, add noise, and might reduce, rather than increase, market valuations. (This is because noise and volatility generally reduce valuations.)

If it ever reaches critical mass, it could mean that any frequent trading hedge fund – not that such a thing is good – would need round-the-world (or at least round-the-clock) traders, so somewhere out there, someone would be awake and ready to put his or her bids in before the masses wake up and learn of the late-night eruption.

As with mutual funds, once-per-day trading in stocks is possible, too, and strikes me as a better-for-society solution. No more human talent and brain power wasted on day trading, flash trading, trade spoofing, and other inanities accidentally birthed by a system designed to channel capital from investors into companies. No more value-reducing volatility injected into the market. No more 9:30 to 4:00 daily market coverage for networks (sorry, guys).

Wouldn’t you rather live in that world? I can’t speak for you, but I probably would.

A limited trading window has downsides, too

The counterargument to an extremely limited trading window is that price discovery becomes a lot scarier. It’s crammed into whatever few minutes it takes to map the bids to the asks. The relative-to-expectations volatility may turn some investors off, and may reduce valuations, too. If you place a market order, you have a much worse sense of the price you’re going to get. If you place a limit order, you may not get filled and have to wait a day to try again.

But you know what?

I don’t care. I don’t care because I’m a long-term investor. Whether I buy a stock at $100 or $102 or $99 or $99.80 makes almost no difference if I plan to hold for five years, 10 years, or longer.

You know who it does make a difference to? The day traders – who shouldn’t really be in the markets in the first place.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.