Weekly Roundup: Inflation, Record-High Stock Market, One Fed Cut (for Now)

Inflation + Stock Market Highs

Pretend you want to buy a thing that normally costs $90, except now it costs $100.

Your thing’s price has been inflated by 11.11%.

The extra $10 may be only annoying if it’s just a one-off purchase, but if you buy many of these things – or other things that have inflated similarly – it becomes more of an issue.

Pretend that later, this thing rises again in price, this time to $108. That’s better, sort of – but still 8% inflation. Then, later, it rises to $112. And then $115. And $117. And so forth.

Two things are simultaneously true:

- Economists and central bankers are celebrating. Inflation has absolutely plummeted – from 11.1% to 1.7% (in the last hypothetical iteration).

- The average person is paying $27 more for a $90 thing than before this inflation kicked in. The average person is not celebrating.

In a sense, both perspectives seem reasonable. I mean, it’s obviously good to stop or slow the “bleeding” (i.e., loss of purchasing power), and prices would be much higher if inflation hadn’t slowed. But it’s also true that overfocusing on the first derivative of something’s price – the rate of change of price movement – misses how how far absolute values have moved.

In real-life terms:

As a CIO, I’m thrilled that the Producer Prices Index (PPI), a measure of wholesale prices, unexpectedly fell 0.2% in May.

As a dad, I’m still paying $18 for my son’s double-meat Chipotle burritos.

But this is not the full picture.

I mean, if prices go up, but my salary goes up even more, I actually benefit from inflation, don’t I? Similarly for my wealth. This point is really important, and it’s often missed (especially by those with an agenda).

Coming out of the pandemic, the Fed lowballed interest rates and boosted liquidity. Great – except the money didn’t go into the day-to-day economy as intended, at least for a while. It essentially “inflated” asset prices – stocks, bonds, and real estate. Because wealthy people by definition hold more assets, this “inflation” (technically, inflation usually means something like generally rising prices, although some hardliners say that it’s any expansion of the money supply) made the rich richer, even if that wasn’t the Fed’s goal.

Eventually, inflation moved into day-to-day things – in a bigger-than-intended way. For a few years, inflation was outpacing wage growth (except in private equity), so people in the day-to-day economy understandably felt sore: Unless they’re investors like you – and if you’re reading BBAE content, you’re likely far more into investing than most people – they didn’t benefit much from the COVID asset price bubble. On top of that, their living costs suddenly outpaced their earnings.

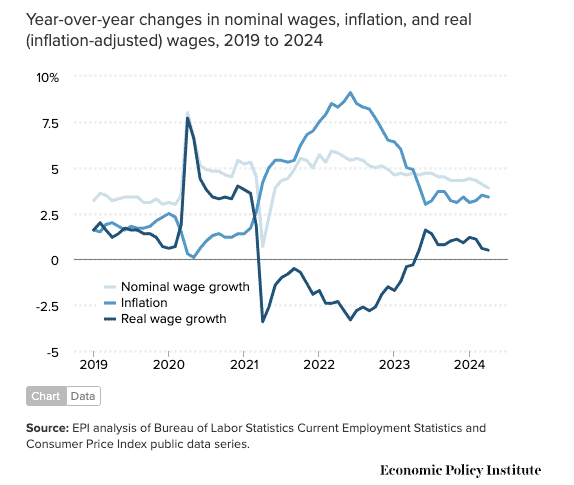

The good news is that the scales tipped more than a year ago, meaning that inflation is no longer a worry to the average American worker, because his or her salary growth is outpacing it.

The Economic Policy Institute graph below illustrates:

So wages up, PPI down, and CPI at least flat (which was slightly lower than market expectations).

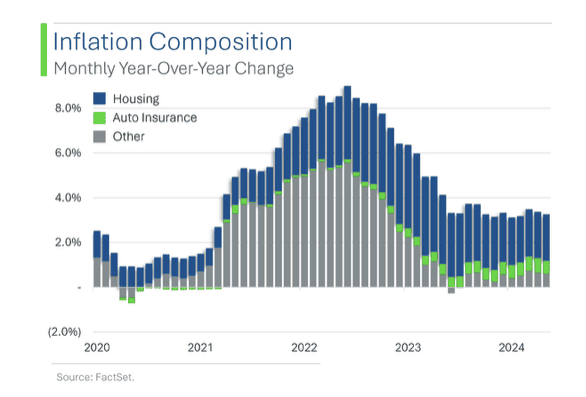

It’s good news. In fact, some guy named “Ryan” – that’s how he bills himself – who writes the StreetSmarts Substack blog noted that if you removed housing and car insurance costs, the year-over-year inflation is just 0.6%, which would be problematically low.

I pay for housing and car insurance, and so do you, so you can’t really remove them, but it’s good news that we’re getting multiple readings of softening inflation, and that current inflation is less and less about “generally” rising prices and more confined to specific things.

It’s been good enough news to send, or at least help send, the US stock market to new highs:

Of course – and I’m speaking as a nonpartisan analyst here – not everyone is happy. And that’s pretty much always the case with inflation.

Inflation, which functions a bit like a tax on spending power (although unlike with taxes, the degree to which the government benefits is less clear), is too tempting not to politicize. Regardless of who’s in the White House and how well the stock market is doing, experts and op-ed writers from the opposing party tend to play up inflation to voters. At the moment, we happen to have a Democratic President, meaning that Republicans are the opposition, but were the tables turned, the probability of headlines similar to the one below coming from Democrats rounds to 100%, so I don’t think there is any higher or lower moral ground here – it’s just politics. (And to be fair, softening inflation may be good enough to send a giddy stock market higher, but inflation is still well above the Fed’s 2% target, which means it’s still officially an “issue,” albeit an improving one.)

If I’m a Democratic strategist, I’m directing attention to points like inflation’s rapid decline, the Fed’s independence (inflation is far more in the Fed’s hands than the President’s, so it’s odd to blame a President), and wages now rising faster than inflation.

If I’m a Republican strategist, I’m bemoaning high absolute price levels, the fact that even though wages are now rising faster than inflation, there’s a lot of catching up to do, and houses and education have become less affordable than a generation ago.

Thankfully, I’m neither. But just like how every stock has a bull and a bear case, and just like how there are two ways to look at the $90-thing example above, inflation has pros and cons and nuances, and I don’t want you to join an inflation “tribe” without understanding how inflation works in the first place.

Balanced thinking wins more often than tribal thinking in investing.

One Fed Cut

I’ll keep this one quick, as it’s as much a public service announcement as a commentary.

The Federal Reserve’s interest rate moves are very hard, and by my standards, impossible, to predict – even by the Federal Reserve.

The Fed is hinting at just one rate cut this year. Headlines touting this abound.

What’s bizarre to me is how quickly humanity forgets that in January of this year, the market was expecting seven rate cuts in 2024 (per the CME FedWatch tool), and was pricing in a 97% expectation of a March 2024 rate cut.

The Fed was predicting a few fewer than seven, but it was still totally wrong, too.

It doesn’t bother me that nobody can predict the Fed’s moves on interest rates. It bothers me, or at least confuses me, that after so much evidence that interest rates are impossible to predict, we still talk about them as if predicting them is a serious thing.

Earth to prognosticators: Nobody can prognosticate this stuff with any reliable accuracy, or at least I haven’t seen it happen.

I think it’s a case of demand creating supply.

What is known, reliably, is that the Fed raises rates to cool the economy, and to reduce inflation. It lowers rates to stimulate it.

The near-unanimous consensus is that the Fed overstimulated the economy during COVID, which eventually led to 9% inflation, but I think Fed Chair Jerome Powell has done an excellent job of engineering a soft landing since that mistake. He’s done it despite a lot of naysayers (the Fed Chair, like any US President, is an easy target)

The “dark” side of the Fed’s shift from an expected seven 2024 rate cuts to one (at least one currently expected; you know by now how these things change) is that the Fed thinks inflation is stubborn and not coming down on its own fast enough.

So the Fed’s position is a bit of a counterpoint to the bright spot of softening inflation I mentioned above.

However, if inflation does keep softening, the Fed may indeed feel comfortable lowering interest rates (technically, the Fed only influences the Fed Funds Rate directly, but that’s another story) later in 2024, meaning that – surprise! – current predictions for one rate cut could be wrong again.

This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. All investment involves inherent risks, including the total loss of principal, and past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions. Neither the author nor BBAE has a position in any investment mentioned.