According to BSD Investing, 46% of ETF inflows in 2022 went into smart beta ETFs – almost half the new ETF money.

Smart beta has fans. It also has detractors. Like Nobel Laureate Bill Sharpe, who coined the investing term “beta” in 1964, and is not delighted about the implication that his original beta may be the dumb beta. (Regarding the name “smart beta,” Bill says: “It makes me sick.”)

Contrasting Bill is Rob Arnott – ever respectful of Bill, and himself an author of more than 130 academic papers – whose Research Affiliates is a smart beta proponent with $130 billion following its strategies.

Who’s right? And what is smart beta anyway?

Let’s start with indexing first.

How to Make an Index the Wrong Way: Price-weight It

There’s a strong argument that the stock market is one of the best inventions in all of humanity. Not in the sense of being brilliantly clever, but because of the impact it’s made.

Yet how to measure it overall?

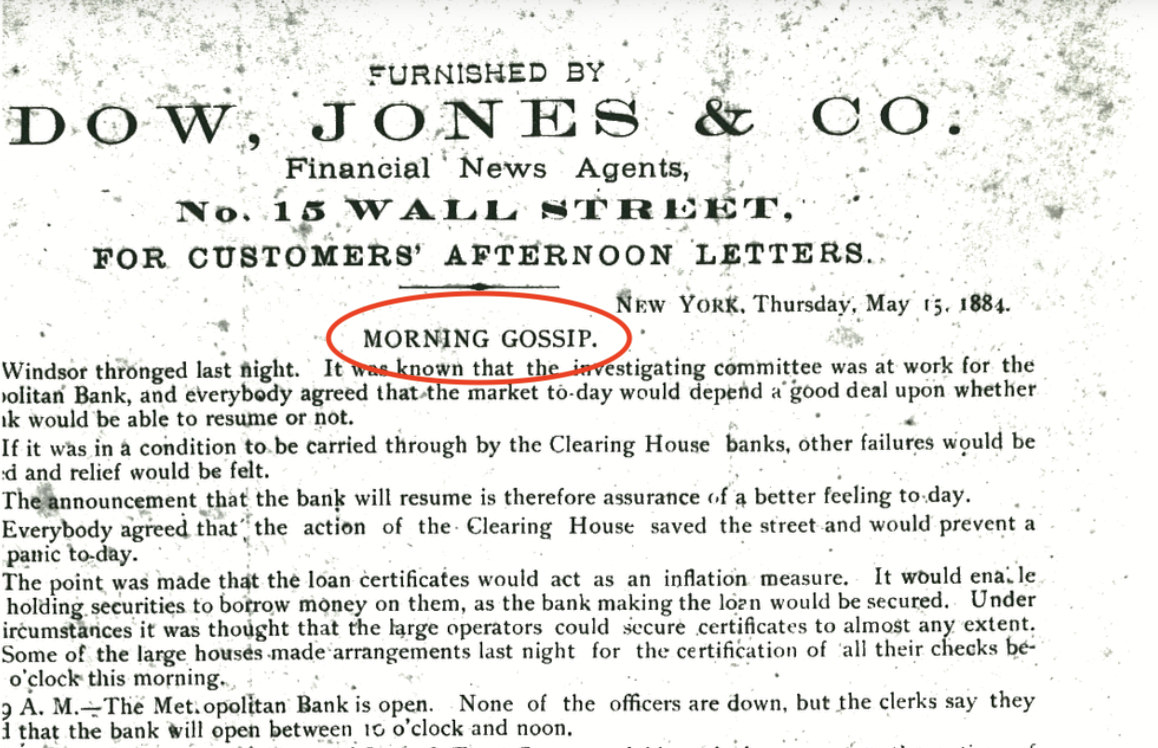

In 1883, business journalists Charles Dow and Edward Jones began publishing the Customers’ Afternoon Letters. This later became The Wall Street Journal, but in the beginning, it was two young guys straddling the line between financial news and gossip.

A year later, Dow and Jones added in a little section tracking the collectively averaged prices of 11 major companies: Nine railroads, one steamship company, and Western Union Telegraph. They literally averaged the prices, adding them up and dividing by 11.

Incidentally, twelve years later, Dow chose twelve stocks for a new index – the Dow Jones Industrial Average – which he computed the same way. Dow bumped their initial railroad-heavy index up to 20 stocks, replacing the two non-railroads with railroads, and called it the Dow Jones Railroad Average.

For a Wall Street gossip column in the early days of the market, a back-of-the-envelope price-weighted index sufficed, and the DJIA’s saving grace has been its selection bias: The companies included were and are large and well-established.

But to illustrate the price-weighting problem, picture a stock market with just two companies:

- Big Company, with $1 trillion in market cap and 1 trillion shares outstanding, so each share is worth $1, and

- Tiny Company, with $100,000 in market and just two shares worth $50,000 each.

If you make a price-weighted index, Tiny Company will totally dominate thanks to its high share price, even though its business is microscopic.

Cap-weighted Indices: The Norm

You can fix this by anchoring not on stock price itself, which is a bit arbitrary, but on market capitalization. The S&P 500 does this.

A “cap weighted” index gives you a read on how the major publicly traded companies in an economy are faring, and in proportion to their sizes. Buying a fund that follows a broad, cap-weighted index is making a similar size-weighted bet on a society’s publicly traded companies.

It’s good overall, and Warren Buffett has instructed the trustee of his wife’s estate to put 90% of her inheritance in a low-fee cap-weighted stock index fund (and 10% in a short-duration bond fund) upon his passing.

Smart Beta: The Market’s Electoral College

But there’s an argument that while a price-weighted index anchors too much on price, a cap-weighted index anchors too much on market capitalization.

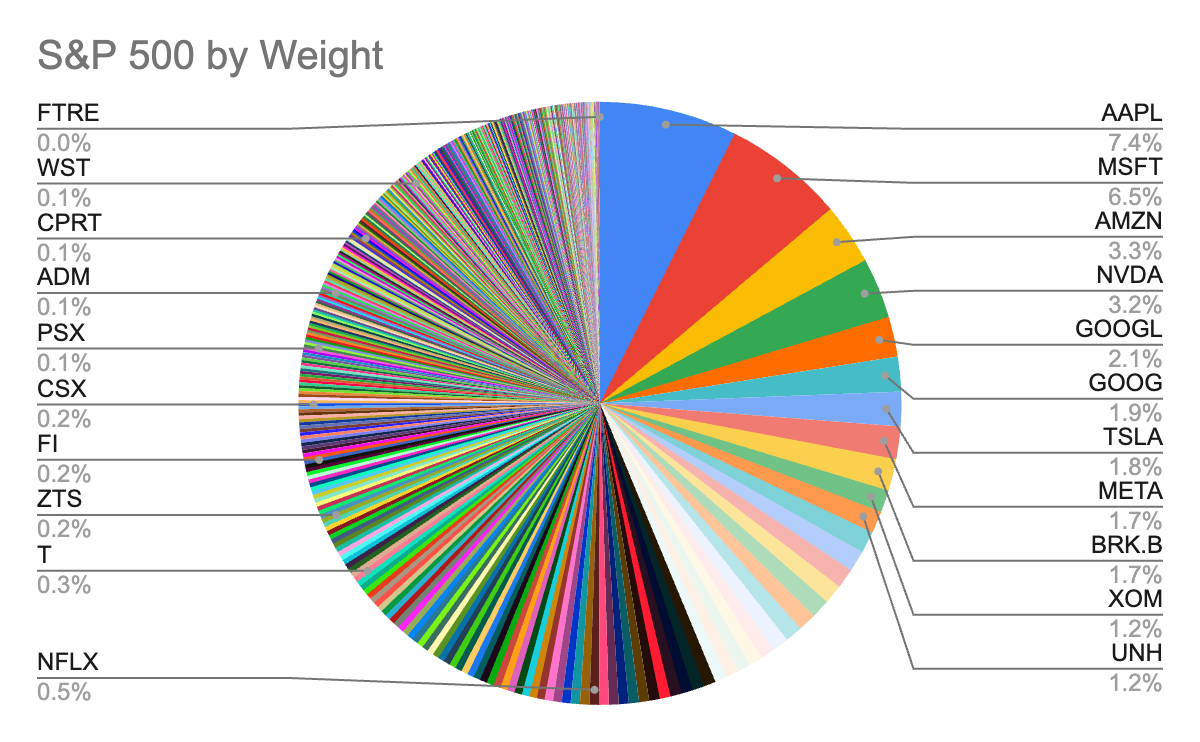

From an investment standpoint, this can be top-heavy. For instance, 95% of the S&P 500 companies are small-cap companies, meaning that – and this has become increasingly true – a handful of really huge companies dominate the index’s movement.

If you’re familiar with the electoral college system, you know it’s designed to give states some “say” in choosing the President by giving every state two baseline votes, regardless of population.

Smart beta, which is actually a marketing term with no precise definition, refers to creating indices using criteria other than market cap. It isn’t exactly the same as the electoral college, but its aim is similar: Don’t let the big constituents overly dominate.

And if they do? The top-heavy tendency of market-cap weighting risks creating a less diversified portfolio than one might expect from a portfolio with 500 stocks. As you can see in the chart, the S&P 500 is diversified, but perhaps not quite as much as you’d think.

As well, weighting by market cap might not provide the best returns. In times when the big winners keep getting bigger, it will. But it risks chasing performance, it fully participates in bubbles, and eventually, the biggest companies run into laws of diminishing returns.

The notion of indexing around factors aside from market cap has been around for decades, but the term smart beta was coined by consulting company Willis Towers Watson in 2006. It’s a play on Bill Sharpe’s use of beta to mean the non-diversifiable “market” risk of a portfolio.

You could, theoretically, choose any non-market cap factors to base a smart beta index around, but common ones include dividend bias, growth bias, value bias (low P/E, for example), small cap bias, or momentum bias.

For example, pretend you like value as a factor; you believe that value will outperform. You have three options:

- You can buy one or more value stocks

- You can buy a fund that holds, say, a few dozen value stocks

- You can buy a smart beta fund that likely holds hundreds of stocks – getting close to the “market,” or at least a market microcosm – but adjusts the weightings of those stocks according to their value-ness.

In other words, with #1 and #2, you’re going out and pursuing value. Bill Sharpe would say you’re pursuing alpha.

With #3, you may be holding the same stocks you’d hold in an index fund, or at least many of them, but just weighting them by their relative appeal on your chosen factor, instead of by market cap or price.

Smart beta, in other words, is like a modified index fund. And so the goal of smart beta tends to be to modestly outperform a cap-weighted index on a risk-adjusted basis.

“When I hear ‘smart beta,’ it makes me sick”

-Bill Sharpe, Nobel Laureate and coiner of “beta” and “alpha”

Sharpe’s criticism is twofold. First is the name itself: “Smart beta” has become an overused buzzword for nearly any passive strategy that’s not mainstream indexing. And some critics say that many “smart beta” strategies are minimally differentiated variants of run-of-the-mill indexing.

But Sharpe’s main gripe is that there’s an element of factor exploitation that’s a zero-sum game. In simpler terms, if someone’s making money from “smart beta,” it’s because someone else is losing money from “dumb beta.”

Sharpe seems to assume that the cap-weighted indexers are the implied losers. If some of the other smart beta skeptics are correct in that plenty of smart beta funds underperform cap-weighted indices, then perhaps Sharpe’s point is blunted just a bit – successful smart beta returns may not be coming at the expense of “dumb beta” market cap indexers; rather, they could be coming at the expense of failed smart beta investors.

Anyway, he’s skeptical.

How Does Smart Beta Perform?

Some people swear that smart beta massively outperforms. Others say that it doesn’t. The discrepancy actually makes sense: if the investment community can’t even agree on what smart beta is, how could we agree on how well it performs?

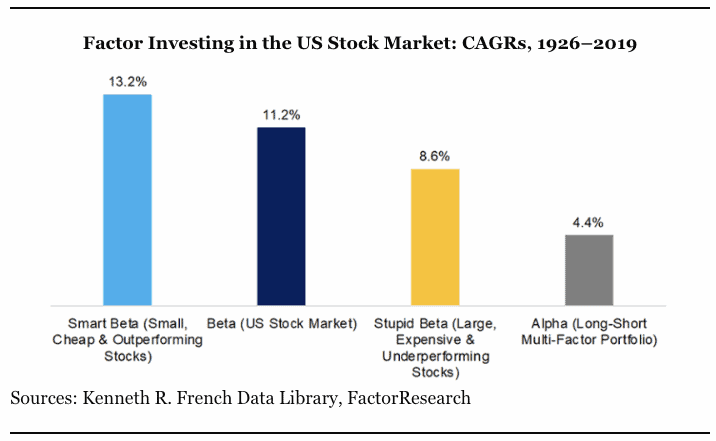

Graphic from Nicolas Rabener, writing for blogs.cfainstitute.org

How to do Smart Beta Smartly

It’s safe to say that smart beta can work, but it does not always work, and it can be overhyped or misunderstood.

Research Affiliates believes that now is a really good time to be getting into smart beta. I suppose a smart beta leader is supposed to say that, but these guys have been open about when they felt smart beta was overpriced before.

Anyway, here are a few of my suggestions:

- Stay in smart beta strategies for a while. The sun doesn’t shine on any factor forever, and nor does the shadow stay. If you’re using factors that have substantial academic research behind them, they should eventually have their time in the sun. But you need to treat a smart beta fund as you would, say, an S&P 500 index fund and hold through the ups and downs.

- Favor well-substantiated smart beta factors. When you have an abundance of data, it’s tempting to dig for some weird, unique factor that the market’s missing. A factor that seems predictive, but which is really just a historical artifact. Stay with the boring stuff like value, cash flows, and dividends (among others) that have been studied time and again for being connected to future stock price returns.

- Think of smart beta as a slightly better alternative (if it works as planned) to a boring index fund. Do not think of it as a ticket to huge returns. Do not attempt to hop from one smart beta strategy to another in an attempt to time factors. If you want to time factors, go ahead, but do it with an “alpha” mindset – proactively chasing high returns – rather than with a baseline-ish “beta” one.

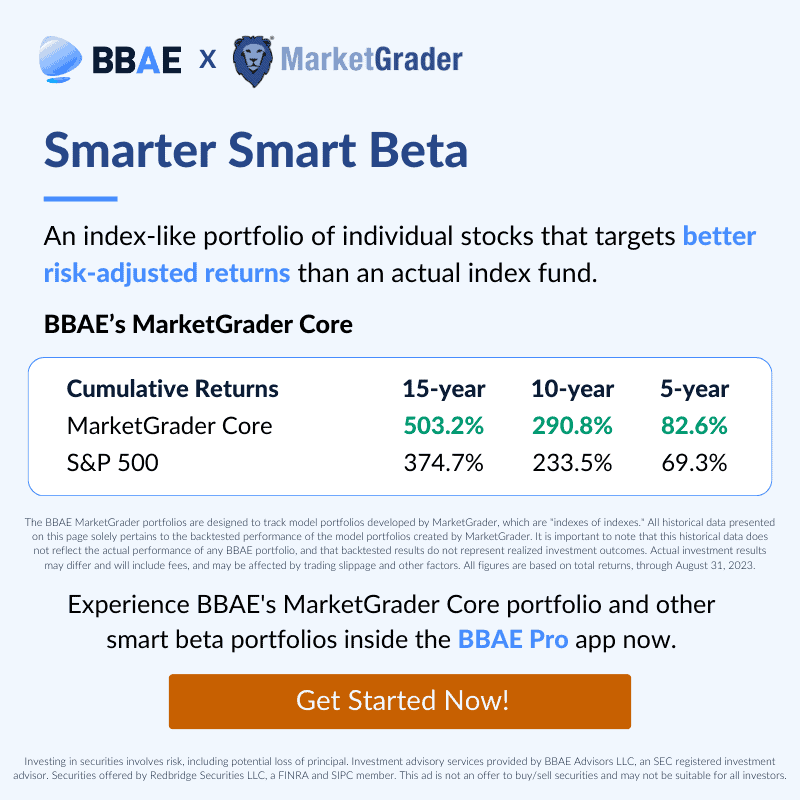

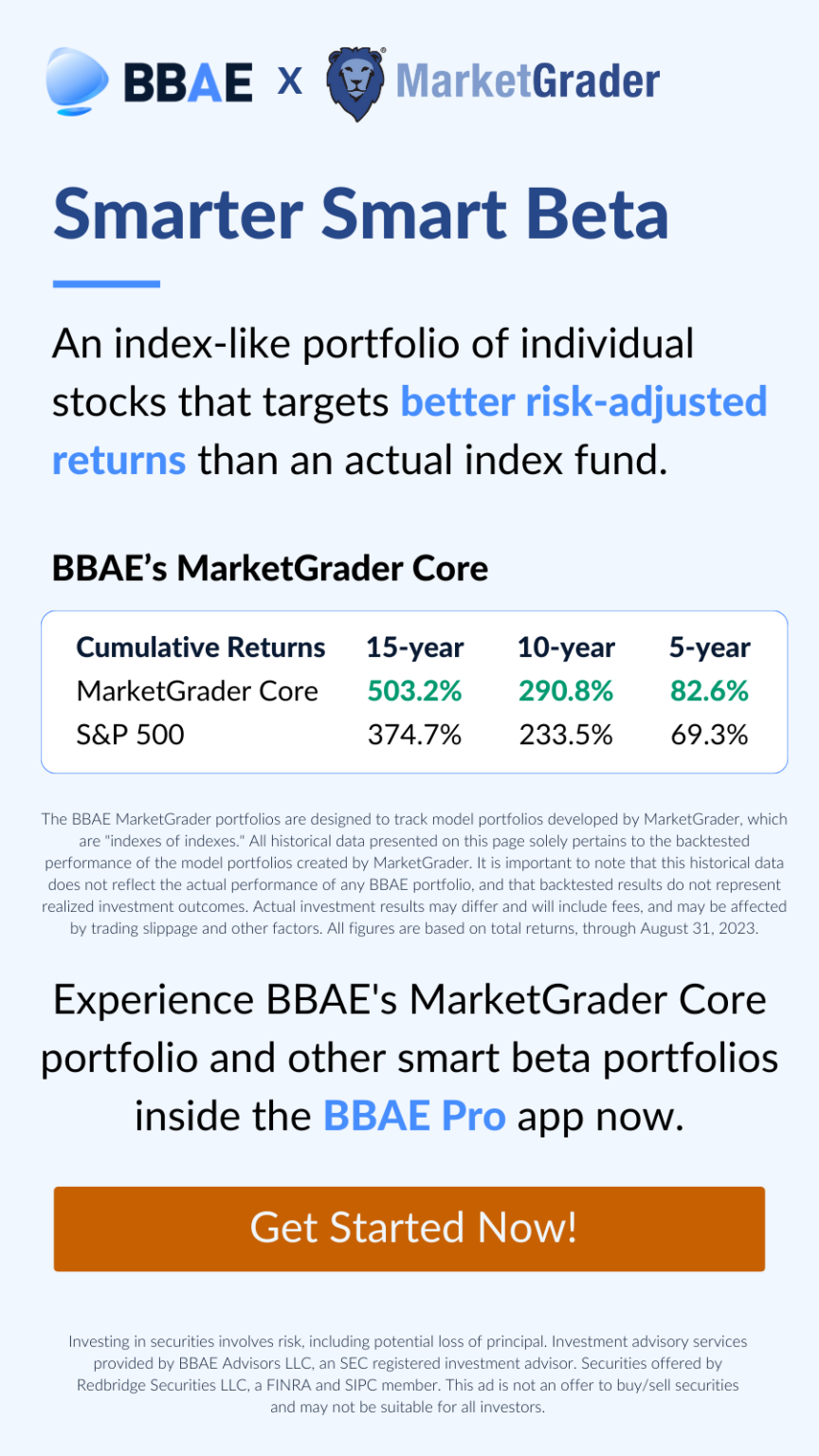

At BBAE, we offer smart beta investing through separately managed accounts, because we have access to smart beta strategies from a company called MarketGrader – the same MarketGrader that powers the Barron’s 400 Index.

We like that MarketGrader uses 24 well-established factors across four categories: growth, value, profitability, and cash flow, and assigns a numeric rating to every stock, and its indices have, on average, outperformed their benchmark, usually with 10- or 15-year outperformance histories.

You can learn more about BBAE’s smart beta portfolios by clicking here.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is neither investment advice nor a solicitation to buy or sell securities. Investing carries inherent risks. Always conduct thorough research or consult with a financial expert before making any investment decisions.